The granite stone that looks like a perfect perch from which to contemplate the ornamental, black swan-inhabited lake is in fact one of many outdoor sculptures by Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica. Photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

If Willy Wonka were a collector of contemporary art rather than a candy man, his factory might look something like Inhotim, a 3,000-acre art park and museum in Brumadinho, a small town near Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Inhotim is the brainchild of Bernardo Paz, a 60-year-old Brazilian pig-iron magnate, whose initially moderate interest in contemporary art eventually became an all-consuming passion. Employing the help of a curatorial team that included American Allan Schwartzman, German Jochen Volz, and Brazilian Rodrigo Moura, Paz bought work from Doug Aitken, Chris Burden, Matthew Barney, Pipilotti Rist, Doris Salcedo, Cildo Miereles, among many others. By 2005 he had amassed a collection so vast he felt compelled to create a public museum for it.

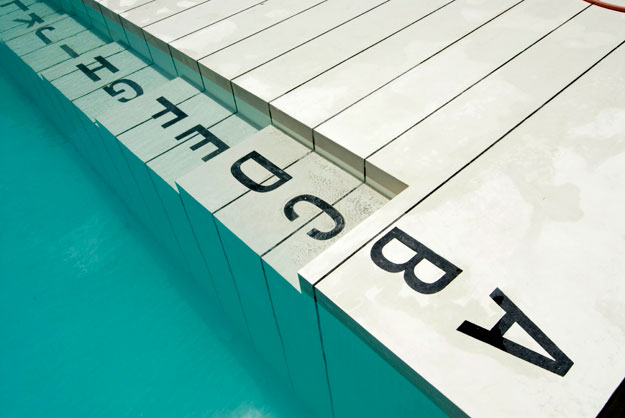

It’s a museum with a difference. Much the same way Wonka’s trees sprout lollipops and mushrooms spurt whipped cream, so do Inhotim’s footpaths, lakes, and VW Bugs burst with color. The botanical gardens that surround the galleries, pavilions, and sites were designed under the guidance of legendary Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle-Marx. The granite stone that looks like a perfect perch from which to contemplate the ornamental, black swan-inhabited lake is in fact one of many outdoor sculptures by Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica. The functioning swimming pool — a refreshing respite from the sweltering heat — is actually an art piece:

Jorge Macchi’s Piscina. Photo: Pedro Motta

Inhotim induces a wondrous, trance-like state, and given its 500+ works by more than 100 different artists, requires at least a day to be seen in full. One of the highlights is Chris Burden’s Beam Drop. Set on a hilltop looking out on distant mountains, it resembles a gargantuan game of Pik-Up Stiks. Burden scavenged 71 steel beams from scrap yards throughout Brazil, hoisted them up on a massive crane, and dropped them into a trough of wet cement. The resulting structure — a collaboration between Burden and gravity — is both gritty and graceful, urban and pastoral.

Another supersized work is Matthew Barney’s De Lama Lâmina. Set inside a pair of mirrored geodesic domes, a hulking, mud-caked tractor clutches a massive, lily-white resin tree in its metal jaws. Is the piece about man’s filthy hands forever meddling with nature? Possibly. Whatever the case, the mirrors do have the effect of embedding the viewer in the scene, thus suggesting complicity.

Matthew Barney’s De Lama Lâmina. Photo: Pedro Motta

But the most Wonka-ish piece of all is Doug Aitken’s Sound Pavilion. Enclosed in a round, modernist pavilion, a borehole is dug more than 600-feet into the earth. At the bottom, highly-sensitive microphones amplify whatever sounds to the surface. Sometimes it’s a faint murmur, others a bellicose grumble. The planet’s bowels, we come to realize, are not terribly unlike our own.

Doug Aitken’s Sound Pavilion. Photo: Pedro Motta