Sandy Beach Resort can been seen on the right. You can see a possible whitewater line of the ancient surf spot on the adjacent islet. Photo: Courtesy SG

I wasn’t the first to surf in Tonga, not by a long, long, long shot. In fact, I didn’t go to Tonga looking for ridable waves, although I certainly knew they existed there. Had for some time, having seen in my junior high library a late-1960s issue of National Geographic magazine that featured an article about the “modernization” of that isolated Polynesian kingdom in Oceania, including a photo of Tāufā ā hau Tupou IV, then king of Tonga, in a snappy little shorebreak, deftly balancing his massive, 6’5″, 400-pound frame on a longboard. I remember thinking that Tupou had to be the only living king at the time who surfed. Over 20 years later, when renowned surf photographer Jeff Divine visited the kingdom with a pack of pros (including Tom Carroll and Kelly Slater) the crew had an opportunity to visit the royal palace for an audience with His Majesty.

“As we approached the king’s compound and were ushered into an adjacent house, we couldn’t help but notice the Yater surfboard tucked away in his garage area,” wrote Divine in a later account. “He described that he often went surfing at his favorite local spot with a flotilla of boats, security and hangers-on, and proudly displayed the shot of himself in National Geographic. He was a regular foot.”

So yes, there was surf in Tonga. Super-shallow, significantly wind-affected, almost as good as some other South Pacific reef pass waves, the inconsistency of which has pretty much kept the island’s lineups under the radar of the booming global surf travel business model. Didn’t matter to me — I wasn’t looking for waves. I was looking for humpback whales.

I’d taken a job directing a government-sponsored, conservation-oriented promotion video featuring Princess Lātūfuipeka Tuku’aho, daughter of King Tupou VI and Queen Nanasipau’u, and her deep spiritual connection with Tonga’s robust population of humpback whales. Whaling having been banned in the kingdom’s water since 1978, Tonga is the only place where swimming with humpbacks is sanctioned and rigorously monitored, the faka’apa’apa, or “respect,” for these remarkable seasonal residents at the forefront of all efforts.

Initially, my job was driving around Tonga’s main island of Tongatapu, spending days and days searching the lush, tropical land and seascapes for compelling shooting locations. I had even checked out the coast near Ha’atafu, Tonga’s only surf resort, a sleepy little operation on the island’s northern curved fingertip, where I got bad-vibed by a scraggly Aussie, who, wallowing in a tattered hammock, very obviously considered the presence of myself and my Tongan film crew as a serious threat to his torpor.

He needn’t have worried — as mentioned, I wasn’t looking to steal any of his precious waves, but was on my way to a surf-less island group in the kingdom’s northern region, my final destination being a tiny speck of perfect called Foa, and the modest Sandy Beach Resort, an impossibly picturesque beachcomber’s paradise set down on dreamy Houmale’eia Beach and lagoon. Here, expats Darren and Nina Rice, two globe-trotting dive-masters and underwater photography experts, put down roots in Foa’s sandy soil, establishing in 2017 an utterly charming, watersport-oriented resort, specializing in diving, kiteboarding and whale swimming.

Did I mention picturesque? This place was perfect for all my cinematic needs, with its swaying palms, pure white sand beach and wide, pristine lagoon, shimmering in a thousand shades of azure. I couldn’t have been more impressed.

“And you haven’t even seen the petroglyphs,” said Darren. “You have to check those out.”

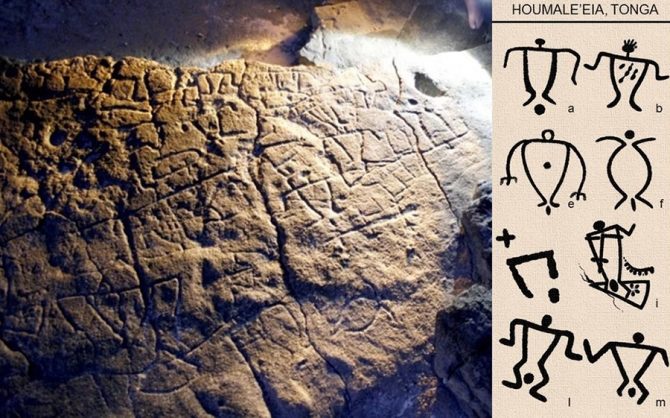

Apparently, back in 2008 a pair of Australian visitors, strolling the beach after a serious northwest blow, stumbled across a newly-exposed chunk of basalt on which was carved over a dozen petroglyphs. Amazing enough, but even more incredible was the fact that, upon examination by various entho/anthropological experts, it was explained that these particular styles of petroglyphs were found nowhere else in Polynesia outside of Hawaii.

“Data from the petroglyph site at Houmale’eia on Foa Island in the Ha’apai Island Group of Tonga are provocative relative to the East/West Polynesian interface,” ran an abstract in New Zealand’s Journal of Polynesia. “And a continued argument for extensive sea-going voyages in later prehistory. The Houmale’eia motif suite has no developmental precedent in Tonga or West Polynesia. Rather, it is typical of Hawaiian rock art dating to the approximate interval AD 1400 to 1600.”

Put more specifically (and less academically) the triangular shape of the human figures in particular, etched alongside seabirds, turtles, lizards and dogs, are unique to Hawaiian petroglyphs, supporting the “provocative” theory that at some time during its history of colonization, Hawaiian voyagers might have made their way back to Tonga, a remarkable navigational feat previously thought to be impossible.

Ancient Rock art on Foa Island. The surfer figure is third down in the right column.

This was all very interesting, but isn’t what dropped my jaw. This came when, after examining the carvings myself, I was provided a treatise by Dr. David Burley, Professor of Archeology at Canada’s Simon Fraser University, who pioneered research at the Houmale’eia site, in which, when outlining the various petroglyphs, he described among other figures a poi pounder, a pigeon-snaring net and a figure of a man standing on a surfboard [my italics].

Okay, let’s think about what this might indicate. That perhaps over 500 years ago, an anonymous, albeit artistically-inclined, Hawaiian was part of an intrepid crew making the extraordinary 3,000- mile, open-ocean voyage from Hawaii to Tonga. Landing on Foa, he or she felt compelled to leave marks of their passing in the soft basalt, as one would at home. And for some reason, felt compelled to include, among the other stone-cold graffiti, a man standing on a surfboard.

“Why?” I wondered aloud, when presenting the revelation to Darren and Nina. “There was no example of anyone in Tonga surfing like this. Stand-up wave riding was practiced only in Hawaii at the time.”

“Well, maybe they were just chronicling their own experience,” Darren suggested. “There actually is a rideable wave here.” He gestured to an adjacent islet across the channel between lagoons. “There’s a fun little peak over there that breaks from time to time, when the swell is from the north. In fact, on days just like this.”

I was into my trunks and borrowing a big board in half a second, paddling across the deep, blue expanse of the channel and onto a shallow reef system on the islet’s tip, where every few minutes a clean little two-foot peak poked its face up into the offshore wind and peeled uniformly toward the palm-lined beach. And I couldn’t help but think how fantastic this was, to be sitting on a surfboard in the very same spot where hundreds of years ago an ancient Hawaiian surfer might have sat, lining up for that glorious first ride after a long trip.

Like me, that surfer hadn’t gone looking for waves in Tonga, but judging by that figure carefully set in stone, was pretty stoked to have found them.