The following is an excerpt from Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku, written by David Davis.

If you spend any amount of time on Oahu, the third largest of the Hawaiian Islands, you cannot help but notice the name Duke Kahanamoku everywhere. There’s Duke Kahanamoku Lagoon, Duke Kahanamoku beach, and the Duke Kahanamoku Aquatic Complex. Theres’ the annual Duke Kahanamoku long-distance canoe race and the annual OceanFest carnival, which raises money for scholarships for the Duke Kahanamoku Foundation and is held near Duke’s, the popular tiki-themed restaurant and bar with a superb view of the ocean.

Not far from the restaurant, on the beach at Waikiki, stands an oversized statue of Duke Kahanamoku. He is depicted wearing swimming trunks, with a surfboard behind him. His arms are extended as if to welcome the many visitors—tourists in T-shirts and sunglasses, surfers with dreadlocks, military personnel in uniform—who have stopped to take photos and read the accompanying plaque.

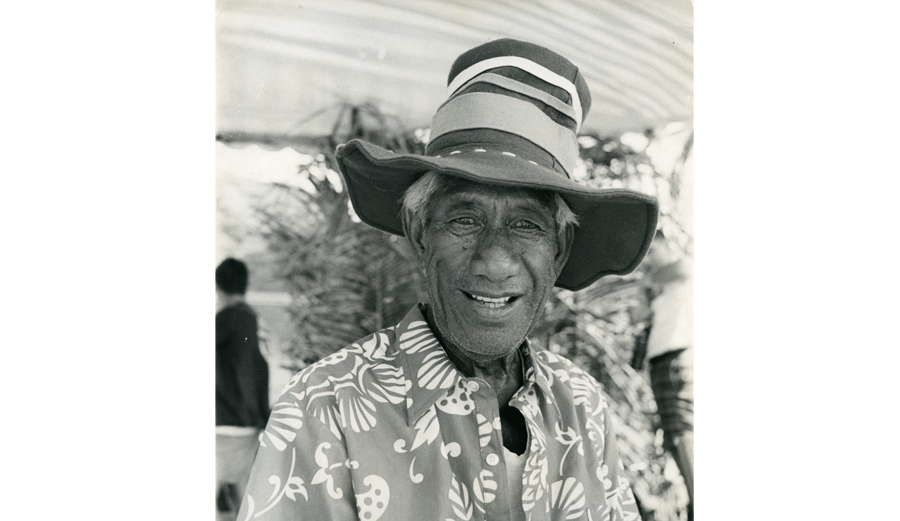

As statues are wont to do, the bronze figure casts an enormous shadow over its surroundings, sort of like the man himself. While he was alive, Duke Kahanamoku was Hawaii’s favorite son. Until Barack Obama came along, no one born in Hawaii was more famous or revered than Duke Kahanamoku.

Duke Kahanamoku and Viola Cady surf tandem at Laguna Beach, circa 1925. From ‘Viola-Diving Wonder.’ Photo: the Paragon Agency.

Legend is a tricky thing. Director John Ford, a friend of Duke’s from his stint in Hollywood in the 1920s, addressed this conundrum in one of the last (and best) Westerns that he directed. The plot of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance revolves around an extended flashback concerning the fates of the two main characters in the movie (played by Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne).

A journalist asks Stewart, a successful elder statesman in the film, to discuss the long-ago incident during which he allegedly killed a scurrilous outlaw named Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin). Stewart proceeds to give the truthful account of what happened and, in doing so, corrects the inaccurate version. After listening to the story, the reporter destroys his notes. “When the legend becomes fact,” he relates, “print the legend.”

Soon after his death in 1968 (or, perhaps, even before he passed away), the legend of Duke Kahanamoku supplanted the flesh-and-blood version. He officially competed in three Olympics, but reports routinely stretched that number to four or five without supplying any concrete evidence. His famous “Long Ride” on a surfboard went from approximately one mile to one-mile-and-a-half. He is said to have introduced surfing to Australia and the East Coast of the United States, even though others surfed there before him. Relatives of the world’s richest heiress, Doris Duke, claimed that Kahanamoku impregnated her, although that seems unlikely. Others have argued that he fulfilled a prophecy spoken by King Kamehameha, the unifier of the Hawaiian Islands, but it is doubtful that this prophecy was ever uttered.

As one of Kahanamoku’s relatives told me, with only some exaggeration, “All you now read ’bout the Duke is false, and for me to divulge the facts would place him in a shallow of the family worth. Let beliefs be if they help the progress of the entities of surfing and aloha, as they need a historical hero for commercialization…Best to leave them to their wallows for it brings no harm and he is left the image of a hero.”

Duke playing an American Indian in ‘The Pony Express.’ Paramount Collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

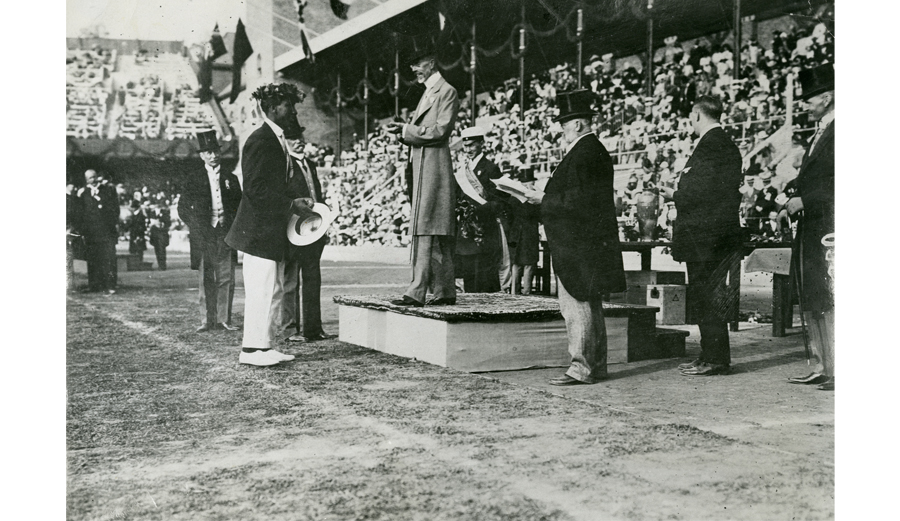

It’s easy to understand why Duke Kahanamoku continues to inspire such talk. His life was one epic ride. In 1890, when Kahanamoku was born, Hawaii was an independent nation. He was just a youngster when Hawaii’s queen was overthrown in a hostile takeover that remains controversial to this day. He first gained fame while swimming for the United States at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, at the time when nonwhite athletes were barred from competing at the elite professional and amateur levels (with exception of a few boxers, jockeys, and collegiate stars).

As a dark-skinned man who represented the hopes and dreams of a predominantly white nation, Kahanamoku encountered and traversed racism and ignorance well before the likes of other pioneers (including Joe Louis, Jesse Owens, and Jackie Robinson). As his swimming success continued into the 1920s, he integrated private and public pools as well as surfing at exclusively white beaches. Photographs of Duke holding white women in his arms while they swam, or bearing them aloft on his powerful shoulders while they surfed tandem, appeared in newspapers around the country. He became the living embodiment of Hawaii and its “exotic” culture—and what a symbol! He was seen as the distillation of everything that was believed to be good about the Hawaiian people: humble yet powerful, sensual and healthy, gracious and noble.

Two-sport star: Duke Hones his golf game while surfing in Southern California, circa 1925. Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library.

Most athletes excel in only one sport. Kahanamoku was also the best surfer of his era. He used his fame as a swimmer to promote surfing, the indigenous pastime of Hawaii and one that few people outside of Waikiki had ever witnessed, much less experienced, before Duke helped to export it. He became the Johnny Appleseed of the waves, collecting acolytes around the globe—from Atlantic City in New Jersey to Corona del Mar in Southern California to Freshwater Beach in Australia. He formed the earliest surfing club in existence and helped formulate the “rules” that govern surfing etiquette today. He practically invented the “Hey, Brah” lifestyle and, despite his lack of business acumen, was among the first sports stars to open an eponymous restaurant-nightclub, to market his own fashion and sneaker lines, and to “brand” himself.

Duke receiving the gold medal from King Gustaf V at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. Photo: James W. Gaddis.

Consider the multiple sports that Kahanamoku directly pioneered: surfing and competitive swimming, most prominently, but also beach volleyball, waterskiing, rowing, sailing paddling, and stand-up paddling (SUP). Consider, too, the myriad activities that surfing has spawned in its wake: skateboarding, snowboarding and their offshoots. When one adds to that mix his contributions to race relations and to the development of modern tourism in Hawaii, as well as his career in Hollywood, it is clear that few athletes, alive or dead, can claim a broader legacy.

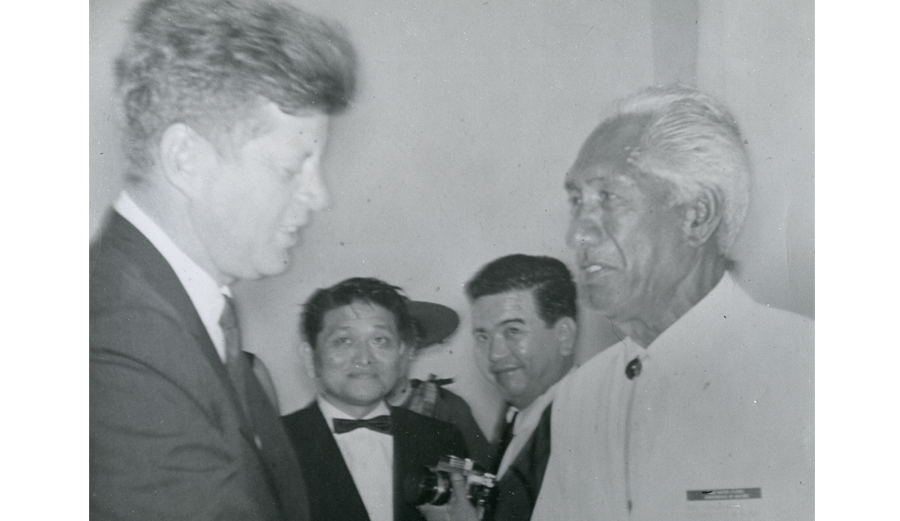

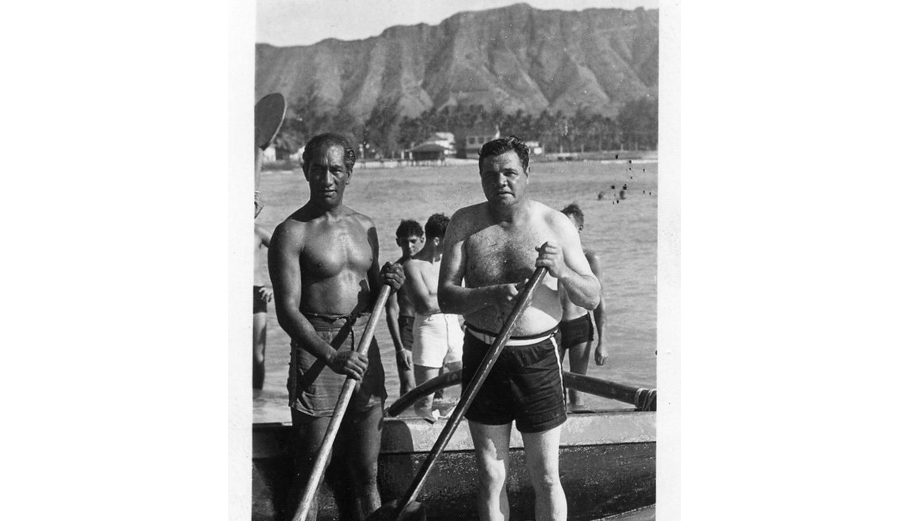

Duke and Babe Ruth at Waikiki Beach. Photo: Linda Ruth Tosetti, Babe Ruth’s granddaughter, archives.

“Duke is Babe Ruth and Jack Dempsey combined down here.” Syndicated columnist Bob Considine once wrote. That was not much of an exaggeration.

Duke Kahanamoku’s uniquely American journey rivals any tale that Horatio Alger concocted—and it resonates more than any lifeless statue. The story begins, as it often does in Hawaii, with the most enduring and beguiling feature: water.

Reproduced from Waterman: The Life and Times of Duke Kahanamoku by David Davis by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 2015 by David Davis.