Editor’s Note: Twenty years ago, Will Henry founded Save The Waves Coalition to mount campaigns and build public support to protect surf breaks across Madeira. Today, Save The Waves Coalition is an international nonprofit dedicated to protecting surf ecosystems. With projects in over 11 countries and counting, STW continues to be motivated by local communities to protect the places they love. This is the story of Save the Waves.

The story of Save The Waves Coalition begins in Madeira, a small island in the North Atlantic.

With towering lava cliffs, waterfalls plummeting thousands of feet, and fierce waves crashing against a boulder-strewn shoreline, for much of its history, it was believed that the island was largely devoid of surf spots.

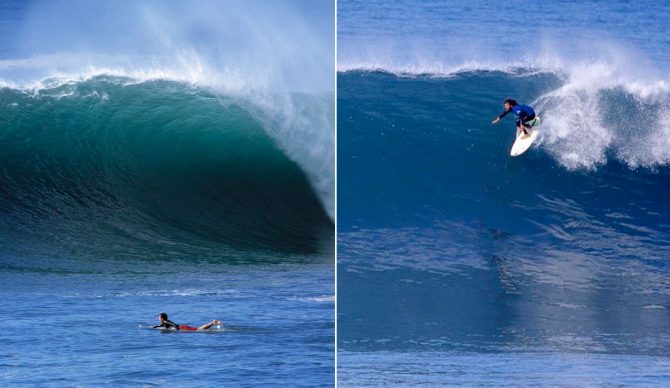

My first visit was in 1995, just a year after the first magazine exposé was published in SURFER. Up until that year, the island had only received a handful of visiting surfers, and had no local surfers at all. The waves there are mostly points that break over large, rounded lava boulders, underneath sheer cliffs that defy proper description. They are not for the faint of heart – most waves on the island start to break at six feet in face height and can handle 30 or more – and getting on and off shore through the boulders is a harrowing experience for even the most skilled of surfers.

As a California-born surfer, Madeira was heaven for me: the rocky shoreline, cool water temps, and lack of coral was familiar territory, and the waves were challenging, high quality, and virtually empty. I returned every year. I remember, on my first trip, asking some Jardim residents about the first time they witnessed someone riding Ponta Jardim. They all told the same story: in the early 1970s a French surfer arrived with his son, and they paddled out and surfed Jardim do Mar for the first time. A few days later, they left – and Jardim did not see another surfer for more than 20 years.

By the early 2000s, there were a few youngsters learning to surf – some from the capital city of Funchal, and some in the village of Jardim do Mar, which holds some of the island’s best waves, including its namesake – once named the best big-wave point break in the world.

The waves that Henry saw were very good, to say the least. Photos: Save The Waves

“You don’t know?” he asked nonchalantly. “They are building a harbor here. In two months, this wave will be gone.” The news struck me like a knife to the chest.

In 2001, some friends and I were surfing a wave on the south coast named Lugar de Baixo. After surfing, we sat on the seawall and chatted with some of the local kids. There was heavy construction equipment on the beach and, as we sat there watching, a giant excavator started digging boulders out of the surf zone and depositing them on the dry shore. The water turned brown. I asked the local kid sitting next to me what was going on. “You don’t know?” he asked nonchalantly. “They are building a harbor here. In two months, this wave will be gone.”

The news struck me like a knife to the chest. I had grown up surfing at my grandparents’ beach house at Dana Strand in Orange County, and for much of my childhood heard stories of the fabled wave that used to break just around the headland: Killer Dana. That point break had been buried under a harbor in the year of my birth. I felt that there must be some way I could prevent Lugar de Baixo from meeting the same fate as Killer Dana.

Upon returning home, I mounted a campaign to try to garner public support against the project. Using the newly found power of the internet, as well as fax machines (yes, remember them?), we bombarded the Madeiran government with pleas to move the harbor elsewhere. Surf-oriented magazines around the world published articles to help us garner more support.

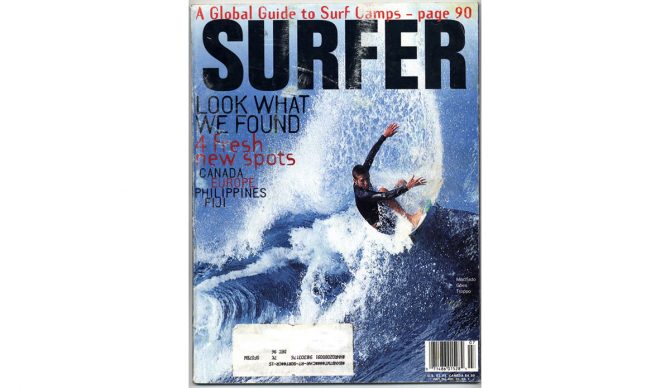

One of my first phone calls was to the editor of SURFER magazine at the time, Sam George. He had actually written the article that was published in 1994 – the first-ever pictorial of surfing in Madeira. I asked him how he chose Madeira as a destination. He told me that a friend of his had tipped him off to the waves there, a French surfer who had once visited in the 1970s and never returned. His name is Gibus de Soultrait, and he was now the editor of two surf magazines in France.

The issue of Surfer Magazine that contained the the first-ever pictorial of surfing in Madeira. Photo: Save The Waves

I called Yvon. “I will write you a personal check for five thousand dollars and will put it in the mail today,” he promised. This was a validation of my efforts so far, and a call to arms.

The story gave me goosebumps: for years we had wondered who this mysterious French surfer was. I called Gibus. He vowed to support. “I have a friend in California who may be able to help,” he said. “I will put you in touch with him.” That friend was the legendary Yvon Chouinard, founder and CP (Chief Philosopher) of Patagonia, Inc., and one of my personal heroes. I called Yvon. “I will write you a personal check for five thousand dollars and I will put it in the mail today,” he promised. This was a validation of my efforts so far, and a call to arms.

I flew back to Madeira as the representative of a new international non-profit called Save The Waves Coalition and met with government officials and the press, trying to state the case for preserving a surf spot.

I spoke about the value it could potentially have for tourism, and of the quality of life for the youth of Madeira. I made enough of a case that, a few weeks later, the government announced that they would relocate the marina. I came home feeling like a hero, but the feeling was short-lived. As one of my mentors, WJ Nichols, had frequently said, “the coastline is never saved, it is always being saved.”

Little did I know that my greatest love, the wave in Jardim do Mar, was next on the list.

(L) Jardim do Mar, from the air. (R) Construction underway at Ponta Jardim. Photos: Save The Waves

The government wanted to build a massive seawall along the shoreline, which would extend tens of meters into the sea, and would either damage or destroy the wave of Ponta Jardim.

To make matters worse, the government had sent people knocking on doors in the village, telling them that a new seawall would mean economic prosperity for their little village of 200 people, and that American surfers wanted to take that away. By the time I returned to Madeira, unbeknownst to me, the village was already fiercely divided.

We marched on the capital of Funchal to protest the seawall, and held a press conference. The President of Madeira, Alberto João Jardim, told the press that surfers were “barefoot tourists,” and that we “wouldn’t even know if a wave broke from the shore to the sea.”

Surfers’ rally to protest in Funchal. Photo: Save The Waves

Our final effort was to hold a protest in the village of Jardim. The cameras were rolling as we arrived in the center square and attempted to set up our tables. With me were a number of visiting surf emissaries, as well as a few dozen local surfers. The townspeople who opposed us showed up in force, yelling, upturning tables, and ripping up our signs. As I raised a sign over my head, I was struck in the face. We were forced to retreat to the edge of town to regroup. What had turned violent, and had seemed initially like a failure, made national news back on the Portuguese mainland.

In the end, a seawall was constructed in Jardim do Mar, albeit on a smaller scale than was originally proposed. The wave suffered, now only breaking well on a low tide (higher tides have too much backwash). The government also managed to bury a wave on the north shore, Ponta Delgada, under a breakwall before anyone could even mount a campaign against it.

(L) Ponta Delgada before. (R)Ponta Delgada after. Photos: Save The Waves

Then I found my email inbox flooded with new requests for help. Waves all around the world were being threatened with similar developments, and Save The Waves seemed to be the only organization with the ability to protect them.

I returned home feeling a bit deflated and wondering what the future held. Then I found my email inbox flooded with new requests for help. Waves all around the world were being threatened with similar developments, and Save The Waves seemed to be the only organization with the ability to protect them.

I had founded an organization that was needed in the world, with a clear mission ahead, and a scrappy, grassroots style of getting things done – which continues to this day.

In retrospect, I realized that one person’s individual actions can actually make a difference in the world, and can motivate others to join the cause. Save The Waves Coalition had been born, and now had a clear mission ahead.

Become a Save The Waves Coalition member here. Follow them on Facebook and Instagram, and subscribe to the STWs YouTube channel here.