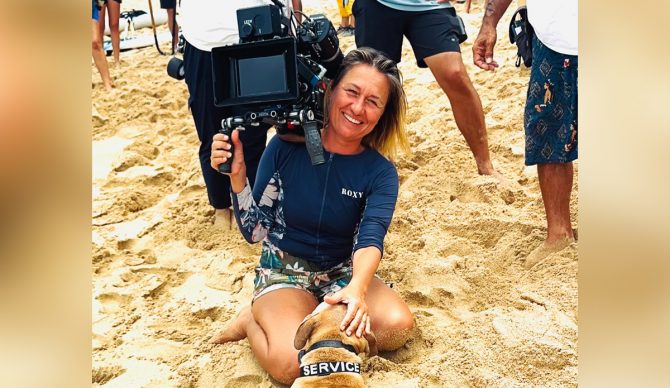

Anka Malatynska leaned on her experience as a surfer while creating the visuals of Rescue: HI Surf. Photo: Anka Malatynska

Rescue: HI-Surf is a series that follows the professional and personal lives of heavy water lifeguards on Oahu’s North Shore. The first season, currently airing on Fox, is marked by interpersonal drama and high-octane rescues inspired by the real-life experiences of Hawaiian watermen and women.

It’s a show that prides itself on authenticity, and no small part of that is due to the work of Anka Malatynska. As the director of photography for the series, she’s instrumental in crafting the show’s lush visuals and exciting rescue sequences. She’s also a North Shore local herself, who originally moved to Oahu to film I Know What You Did Last Summer, but stuck around for going on five years now.

It comes as no surprise that Anka would be drawn to the series, because she has extreme sports in her blood. Her father was a mountaineer who died in the Himalayas before she turned two. Growing up, Anka and her brother were told that they could do any sport they wanted, but they weren’t allowed to rock climb until they were 18. She jokes that the rule was “You can stay out all night, but you can’t rock climb.”

However, a different sport found her instead: surfing. After moving from Poland to the United States, Anka’s family went on a trip to Southern California, where she saw the surfers of San Onofre and immediately knew she wanted to be like them. Years later, as a 17-year-old exchange student in Chile, she finally got to realize that dream, learning the ropes in the land of endless lefts (and taking her share of beatdowns in the process). She’s followed the waves ever since, whether surfing in Topanga while living in Southern California, or honing her skills during a stint in Nicaragua during COVID.

We spoke to Anka about creating drama on both land and water, tackling the logistics of filming on the Seven Mile Miracle, and what happens when your film crew arrives to find an endangered monk seal sitting right in the middle of your set.

The show looks great, congratulations. All the water photography is amazing.

That is all Don King, who’s our water photographer. I did some water work, but we really had a separate water unit that was working in tandem with the rest of the show. That water unit acted like a stunt unit sometimes. I did shoot some water stuff, but not all of it. [Don] is a legendary water photographer in Hawaii.

Rescue: HI-Surf has been pretty intentional about of trying to hire locally. How do you think that that helped the production and specifically the camera department?

I got to put together the team that I’ve wanted to put together since I left I Know What You Did Last Summer. On [NCIS: Hawaii], I inherited a team. On this, I got to pull in all the people that I love that weren’t working on NCIS. It was like working with my friends and family.

What island are you on?

I’m on Oahu and all of our filming took place on Oahu. I would say it’s very true to location. Not only did we hire locally, we also intentionally kept the smallest footprint possible as a filming company.

I’ve never quite shot a television show like this. It was more like shooting a large independent film. We really limited the amount of equipment that we had, so that we could shoot on the North Shore, which is a really tiny place, connected by one two-lane road. There’s a lot of issues over the tightness of that geography, but we wanted to represent the true place.

Then a lot of our water work took place on the west side of Oahu. That’s mostly for the water clarity. When you shoot in Hawaii, a lot of the time when you’re shooting water scenes, you’re working off the west side of Oahu.

Photo: Anka Malatynska

That much work on location must be difficult.

That’s why we’re working with the top water people in the world, including Brian Keaulana. Whenever they’re shooting out in the ocean, there’s rescue skis, there’s a shark drone.

Part of the show is also about embracing the chaos. Everything is moving. Everything is changing. That was very much the MO for us on land as it was in the water. I’ve learned not to anticipate, but to be really present in the moment. Sometimes it would be like, once we get to the beach, depending on how the tide is, we’re either going to go 500 yards with the set in one direction or 500 yards in the opposite direction, depending on what keyhole in the reef we’re using for entrances and exits.

We had things like “Oh no, we chose this location, and now there’s a monk seal that beached itself in the middle of our scene and because monk seals are a protected species, now we have to move our scene 50 yards away.” It really was a dance with nature the whole time.

The rescue sequences are big banner moments in the series. How did you approach filming them?

It’s pure chaos when we film those sequences, and I feel like part of that chaos then becomes the energy. Usually, when we’re shooting those sequences, we’re a much bigger unit. It’s the two water cameras and the two land cameras and we’re leapfrogging them. It also means that then there’s a much larger footprint of people on the beach. You have this pile of 60 people trying to follow the director and the DP and the actors.

Every time, we would go through this step-by-step process of how they would carry them out, what we would do medically. It was really important for a John Wells show to keep true to the process, so there’s a lot of process work. Everybody’s walking through the mechanics of it, and oftentimes at a certain point we’d be like “Let’s just start rolling.” The first rehearsal was really the first take. And that was the part of the process.

What is a sequence that really stood out while filming the season?

There’s a scene that we did in Waimea Falls. There’s rarely any lightning or thunder on Oahu, but that morning there was a torrential rain storm. There was lightning, there was thunder. We were supposed to do a tandem land/water unit and we were basically shut down for six hours. We thought we would have to stop for the whole day.

We also thought that where we were was going to become a flood zone. I guess Lost got washed out of there years ago and lost a bunch of equipment. So, there’s no cell phone reception, there’s lightning, there’s barely any visibility, and we’re supposed to shoot a romantic scene.

Then the flood warning got pulled back. The dam wasn’t going to breach and they gave us permission to go in and shoot for an hour, but it was no longer in the water. Funny enough, it actually made a better scene, being out of the water against the waterfall rather than in the water.

I like to say this a lot: In film, a lot of the time, the limitation is the gift. I did laugh a lot during the making of the show that, while that’s my favorite saying in many circumstances, this show really took me to the edge of wondering whether that’s a good philosophy at all.

How did your personal experience as a surfer affect your work?

It made me really sad when I didn’t have time to surf because we were shooting. I did shoot some of the water stuff and just being comfortable in the water and being at home in the water was really important. Being able to see currents and the movement of the ocean and keyholes and understanding the language of the water unit, that was all really important.

Because it was season one and I was working so hard, I didn’t paddle out at lunch as much as I hope I will during season two, now that things are more dialed in. I would tell my camera department that “You guys are beyond the top one percent, because you are the only people who are working on a series and paddling out and surfing on the North Shore during your lunch break.” That’s a very, very tiny minority of the world.