A hammerhead caught in a shark net. Photo: Adam Baugh/Speakupforthevoiceless.org

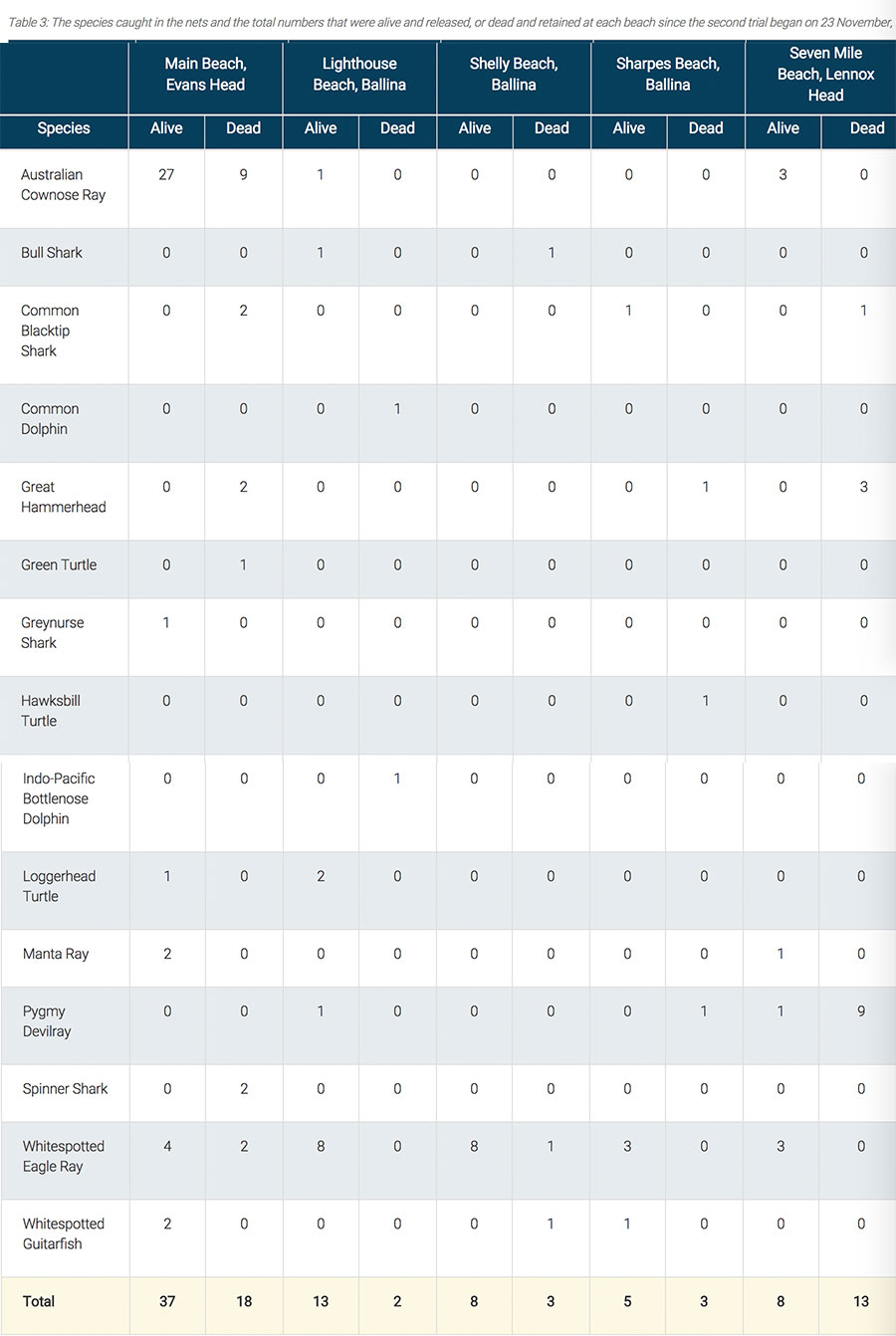

Shark nets along Australia’s coastline have long been a source of debate, and recent studies off New South Wales will almost certainly fan the flames. In January and February, a single bull shark was caught, while 55 other animals were either caught or died in the nets. Since the trial began in November of 2017, only two bull sharks have been caught, one alive and one dead.

The study, released by the NSW government’s Department of Primary Industries, reported that over the two-month span, four great hammerheads—a harmless species that is on the vulnerable species list—were captured along with two dolphins. Also on the list is 83 rays (whitespotted eagle rays, pygmy devil rays, cownose rays, and, manta rays) and five turtles (green, hawksbill, and loggerhead), among various other species.

The trial, which began on November 23, 2017, releases monthly reports on the catch. It’s the second set the government has done. Since then, only two bull sharks have been captured, and interestingly, no great whites.

The first trial, which was conducted from December of 2016 to May of 2017, concluded in a similar manner. Target sharks accounted for only three percent of the total catch, while rays took up 67 percent. Turtles and dolphins were six percent, non-target sharks were 15 percent, and nine percent was listed as “other”.

The nets, of course, are supposed to catch target sharks. They aren’t a barrier that encloses the beach, as is commonly thought. “The nets used in the NSW shark meshing (bather protection) program do not create an enclosed area within which beachgoers are protected from sharks,” wrote Leah Gibbs, a senior lecturer in geography at the University of Wollongong. “They are fishing nets, which function by catching and killing sharks in the area. Nets are 150 metres long, 6 metres deep, and are suspended in water 10 to 12 metres deep, within 500 metres of the shore.”

As is to be expected, the latest round of trial results has angered the program’s opponents. “How many more months of damning data will it take for the government to finally realise this experiment is an utter failure and shut it down?” Humane Society International marine scientist Jessica Morris asked The Guardian. “Non-lethal alternatives to nets are available and we cannot afford to keep killing harmless and protected species for the next 18 months or more.”

The government, however, is aware of the issues with the nets. It is in the process of developing modified nets that could potentially reduce the bycatch numbers. Modifications include larger mesh which would allow smaller animals to swim through the nets and positioning nets near the surface, which would allow things like turtles and dolphins to breath when they’re caught—as long as they happen to be caught in the part of the net close to the surface.

Despite the results of the trials, residents in the area do, however, feel safer. “An independent community survey carried out before the first mesh net trial clearly indicated that Ballina Shire and Evans Head residents were more positive than negative towards the trial of nets,” said Primary Industries Minister Niall Blair to The Guardian. “[They] felt that it increased their feelings of safety for their families and the community.”

Be that as it may, another study done by an upper house committee found that peace of mind didn’t actually mean that beachgoers were safer. “The committee is concerned that a heightened fear of sharks has led to responses that may calm the public and appear to provide an effective response but which are not verified by scientific evidence,” the committee concluded. “It is impossible for lethal shark control measures to guarantee public safety.”