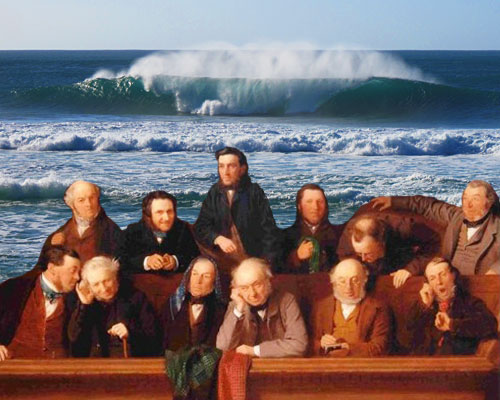

The Jury (by John Morgan) commences deliberation at Pipeline.

Necessity can be the mother of invention, and problems lead to solutions. Here’s a problem: World Tour judges have a hard road to travel. The pay is minimal. There’s no real career path if they drop off the tour, and continuity in family life is extremely difficult. They also bear the brunt of the tensions surrounding how world-class surfing can be consistently and fairly assessed and judged to the satisfaction of the crowd and the surfers. It’s not a happy task when there is no runaway winner of a heat, and reputations, careers, titles, and the very question of what makes good surfing is itself in question.

One possible problem with professional judging has been summed up in the pretty rough, catchall statement: “If you pay peanuts you get monkeys.” A different problem is that, even if traveling judges were paid better, by using increasingly isolated and specialized judging criteria the whole ballgame sometimes becomes so esoteric and complicated that Joe Normal surfer on the beach is left puzzled in shock at some decisions. For example, he could be left wondering why the surfer that brought “Oohs!” and “Aahs!” from the crowd doesn’t top the score of another surfer with an inside shore break maneuver that looked gymnastic. The technicalities might not persuade him. Instead he may feel as if the judges and pro surfers are all in a clique together: one that he doesn’t understand.

Thinking outside the box, here’s another way to look at this:

The principle of trial by jury is that twelve “good men and true” will arrive at a wise decision. Surfing heats isn’t more important than life and death courtroom decisions.

A cross section of twelve local surfers could judge a heat and discount the top and bottom three scores. Give the competitors some input into which judges are chosen just as the prosecution and defense get a say on jury selection.

Personally, we’d like to see much less emphasis on rodeos and tricks – surfers picking the most exciting waves on any day and riding them with power, adventure, style and grace always bring people to their feet. Selecting a representational cross section from the local surf community to judge events would reward mainstream progressive surfing and marginalize the more erratic, wild, gimmicky tricks. That’s our opinion; maybe twelve “good judges and true” would decide differently.

There are obvious problems with this. World Tour contests can spread over a long waiting period during which judges have to be available and free from other work obligations. Financial compensation could be paid, and this wouldn’t involve the cost of flying in judges as it does now.

Strong words would need to be spoken to minimize the problems of local favoritism, although discounting the top and bottom three scores should help eliminate this.

Ensuring a wide community cross-section of surfer judges would help avoid two more problems. First, this prevent World Tour surfers from familiarizing themselves with the judges’ technical expectations, and encourage them to surf with their own creativity and flair. The jury would be too broad to do this. As long as riding a short board has been part of their surfing experience, we count them all as eligible. Secondly, insisting on a wide cross section would prevent the people who end up on the jury being the ones who’ve socialized best with the people running the electoral process.

Does judging need to be so standardized, or so broad, that World Tour surfers wouldn’t need to pander to local surfing cultures’ expectations? I don’t think so. That’s part of the game. Pipe locals know what makes the grade at Pipe. Trestles surfers know what gains respect in the water there. We think officials can get too intense, too specific, and try to be too scientific. We think judges can be guilty of over-complicating surfing as if understanding good surfing is like understanding nuclear physics where we need Einstein to produce a theory about it. We don’t. That’s why a jury of twelve “good and true” made up of your average surfer Joe and surfer Jane, are reliable arbitrators. They can decide over and above the surfing scientists, the technical specialists, and a stream of experts.

A traveling ASP representative and a World Tour surfers’ representative could work with the representatives of a local surf area using an agreed cross section surf community profile to select the jury. A jury of eight could also work, with the two highest and the two lowest scores being dropped. Court jury duty is a privilege. It would be no less a privilege if a local surfing community gets asked to provide a jury for a world class surfing event; people would rise to the occasion and the jury gets the last word: surfing for the people, judged by the people.