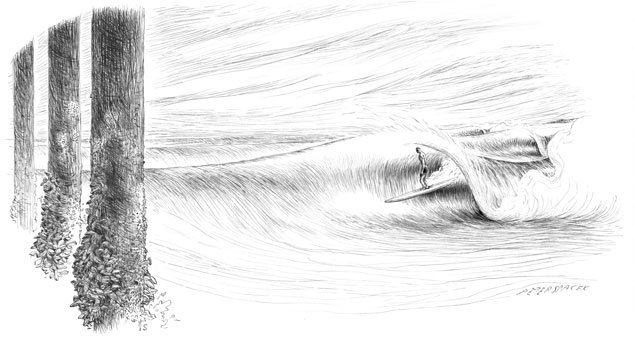

An artistic rendering of Nick Gabaldon's last wave at the Malibu Pier. Gabaldon is credited with being the first documented African American surfer. Art: Peter Spacek

“The second period when swimming became popularized and democratized was in the 1950s and 1960s sixties,” says Wiltse. That era of popularization primarily occurred at the (literally) tens of thousands of private club pools in the nation’s burgeoning suburbs. As some historians have pointed out, the Post-War suburbs were lily-white. So, we basically see a replay of what happened in the first swimming pool boom – tens of thousands of new pools contributed to further the democratization and popularization of swimming, but all this was occurring in institutions to which Black Americans had no access.”

This era differed slightly from the first in that the segregation was often a function of larger social norms instead of explicit racism. “There was some overt racism during this period in denying black Americans access to pools, but in large part it was more a consequence of residential segregation,” says Wiltse. “…These pools were located in neighborhoods that Black Americans simply didn’t have access to.”

The late 1960s saw a public pool building spree in low income, racially segregated neighborhoods, but unfortunately for would-be black swimmers, the structures were little more than glorified bathtubs, often no more than a few feet deep and designed more to appease lower class, urban populations than to provide quality spaces for people to swim.

During the same time period that they were denied access to pools, American blacks weren’t doing any better with beaches. Due to the growing concept of coastal land as valuable leisure space, as well as the same White/Black sexual concerns that surrounded swimming pools, Black Americans were often only allowed to swim at out-of-the-way, segregated beaches in the American South.

In the beginning of the 20th century, almost all of the blacks in America lived in the South. However, the Great Migration, which would see the fanning-out of some six million Blacks over six decades to all parts of the nation, changed all of that. Many African Americans found that coastal areas were just as segregated in other parts of the country as they had been in the South. Frederick Douglas’ son Charles and his wife, Laura, founded a Black beach resort at Highland Beach, Maryland after they had been refused service at the nearby Bay Ridge resort based on race.

Any Black person who wished to move into a coastal (read: “White,”) community faced an uphill battle. It was often difficult for them to get loans for houses based on their race and even more difficult to find real estate agents willing to show them houses in White neighborhoods. The residents of these neighborhoods often put racial covenants on their homes, which made it illegal to sell the property to people of other races. Although they were ruled unconstitutional in 1949, many racial covenants still sit like ghosts on house deeds to this day.

Efforts by Black people to develop directly on the beach, either residentially or commercially, were even more contentious. Once such development, a proposed leisure and resort facility for Black people in Santa Monica was opposed in courts by white property owners who organized themselves into “protective leagues” designed to “eliminat[e] all objectionable features or anything that now is or will provide a menace to the bay district,” Alison R. Jefferson, a Doctoral Graduate Student at UC Santa Barbara wrote.

“African Americans were squeezed out from living on the coast early which hurt their relationship with the ocean,” Jefferson says. “The beach in Santa Monica was seen as a gathering place. African Americans didn’t just go to swim, they went to see their friends.” It was that tendency to gather that local white people found threatening. “People didn’t bother them from a recreational access standpoint if they were individuals, but they definitely bothered them when they were in groups.”

The movement of many blacks away from the beach was a gradual process, according to Jefferson, that included a range of different motivations. “There was hostility towards them going to the beach so they just stopped going,” she says. “When you have activities where people are pushing you out and property prices are going up and restrictive racial covenants are imposed on properties, exclusion changes the dynamic of the community. In Santa Monica there are still old African American families that own property but most of the community started moving more inland.”

Would-be black beach goers in other areas faced similar issues. A resort called Bruce’s Beach in Manhattan Beach operated for twelve years in the face of repeated intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan but was eventually killed by the state in order to create a park. Another resort called the Pacific Beach Club in Huntington Beach was simply burned down by arsonists when it was near completion.

“Swimming in the United States is a cultural phenomenon,” says Wiltse. “Cultures operate by being passed down from generation to generation. White Americans learned to swim and enjoy the water during ‘20s and ‘30s. They then passed that down through family and friends. That just didn’t happen to Black Americans…swimming never became part of their recreational culture as it did with whites.”

Culture is a fragile thing. In the late 19th century, surfing culture almost died out due to Western cultural imperialism in Hawaii. It survived thanks, in part, to people like Duke Kahanamoku, George Freeth, and others weren’t afraid to cross racial barriers in order to share something pure and fun with their fellow man. I don’t think Black Americans need similar cultural ambassadors to develop a swimming culture (and a subsequent surfing culture), because regardless of what the statistics say, they have had one all along. It has endured over 400 years of assault from slave owners, Jim Crow policies, real estate segregation, and informal racism. Still it continues, beleaguered but by no means broken to this day. Of the many obstacles Black swimming culture still faces, perhaps the most daunting, is the very notion that it does not exist: that a Black person enjoying the water is anomalous, that surfing and swimming, and all water-based activities are somehow written into the genetic code of Caucasians and omitted from that of Blacks. It is our responsibility, as surfers and as people of all races, to change this discourse. The question should not be: “Why don’t black people surf?” It should be “Why wouldn’t black people surf?”

The preceding article is part of a month-long series celebrating African American surf culture. Also see, Black Surfing Association President Tony Corley’s “I Have a Dream,” and the mini-documentary 12 Miles North by Richard Yelland.