A conceptual image of what Bertish will be crossing the Pacific Ocean on. Image: Tom Servais

Chris Bertish is about to do something that could be viewed as crazy. He’s going to cross the Pacific on a hydrofoil board with a wing. Alone. If all goes according to plan, he’ll leave the coast of California from Half Moon Bay in June, wing across the Pacific, and end up on Oahu in July. He’s estimating it’ll take him around 50 days, completely unassisted.

Bertish is an incredibly accomplished human being. He’s done more in his life than most, and he’s done those things because he simply refuses to quit. It’s an old cliché, but the saying “failure is not an option” could have first been uttered about him. He’s a champion big wave surfer, a stand-up paddle world-record holder, a waterman par excellence, an author, a motivational speaker, and a staunch environmentalist.

Incredibly, the Pacific crossing he’s planning, dubbed the TransPac Wing Project, won’t be Bertish’s first go at crossing an ocean. On the morning of March 9, 2017, Bertish completed the final strokes of his stand-up paddle voyage across the Atlantic. It took him 93 days and around 2.5 million paddle strokes. Twenty-two hundred hours alone in the vast sea, paddling for the horizon, mostly at night to avoid the sun’s harsh rays. The journey, which began in Morocco, was originally supposed to end in Florida, but, as could be expected when crossing the Atlantic on a modified SUP, he ran into bad weather and technical issues that would have forced most people to give up. Instead, Bertish diverted to Antigua, some 1,500 miles south of Florida. He still completed his mission across the Atlantic, crossing 4,000 miles of wild, untamed ocean. There’s a soon-to-be released film called Last Known Coordinates about the endeavor coming out in a few short months that covers the journey, using footage Bertish shot himself, and it’s bound to be harrowing, insightful, and inspiring.

Bertish began his journey at about 175 pounds and finished at a little over 140. He ate what could be described as astronaut food — freeze-dried packages — as well as biltong (he is from South Africa, after all), a bite of chocolate, and an electrolyte powder/recovery shake mixed with water once a day. “It was a pretty scientific approach to nutrition,” Bertish said. “I’ve been fortunate to have done this stuff before, and I’ve learned a hell of a lot from that – and applied it to this project.”

Now, a few years after the Atlantic crossing, he’s got his sights set on the Pacific — but this time, on a wing and a foil. He’s doing it on the same board he crossed the Atlantic on, save for a few (major) modifications. You might be thinking that he crossed an ocean on a plain old stand-up board, but you’d be wrong. The ImpiFish is unlike any other craft in the world.

“It’s very unique,” he told The Inertia in 2017, a few months after completing his trans-Atlantic journey. “There’s nothing like it that really exists on the planet. It was designed for one goal and one goal only: to get me across the Atlantic Ocean in one piece.”

The ImpiFish was inspired by rowboats built to cross oceans: a tiny cabin in the hull to protect him from the elements, a full navigation station including a chart plotter and devices that show his speed, direction, depth, radar and radio. There’s a bilge pump, a water purifier, and a whole whack of solar-powered navigation lighting and battery banks. It’s a wild creation that would only ever be built from the mind of Chris Bertish. Now, however, the craft is in the process of being redesigned to get him across the Pacific, as well. It’ll be outfitted with a foil setup.

There have been more than a few Pacific crossings, but doing it entirely alone on a 14-foot board is something hard to wrap your head around. For Bertish, it’s a pretty simple equation: the more he’s relying on other people, the higher the chances of failure are.

“No matter how I package the fact that I have no support craft with me,” Bertish told me in his thick South African brogue over a crackly phone connection, “people find it hard to process. But as soon as you add on a support craft, you instantly add the possibility for expedition failure. For a craft that could do it, you need between five to eight crew members. The more people you have with you, the less chance you have of a successful outcome. So if or when the support craft fails for whatever reason, if they have to turn back, no matter if I’m in the best possible position to finish it, I can’t because I’ve built the whole project around my support craft.”

It’s an exercise in supreme self-reliance. “I don’t want to be relying on someone else when there are so many other elements that could possibly go wrong that are out of my control,” he explained. “With all the things that I’ve done in the past, the only person who’s never let me down is myself. If I take all the knowledge I have — the surfing, the sailing, the heavy weather, all the ocean stuff that I’ve learned — and if I’ve built-in redundancies and backups and backups for every one of my major systems, there’s no reason why the project should fail… unless I give up, and I’ve never given up on anything in my entire life. I’ve never let myself down.”

Despite all that confidence — or perhaps it’s the reason for it — crossing the Pacific isn’t something Bertish takes lightly. The amount of research and preparation that goes into an expedition like this is staggering. To Bertish, the hard part isn’t the actual crossing itself. Instead, it’s the months or years leading up to it.

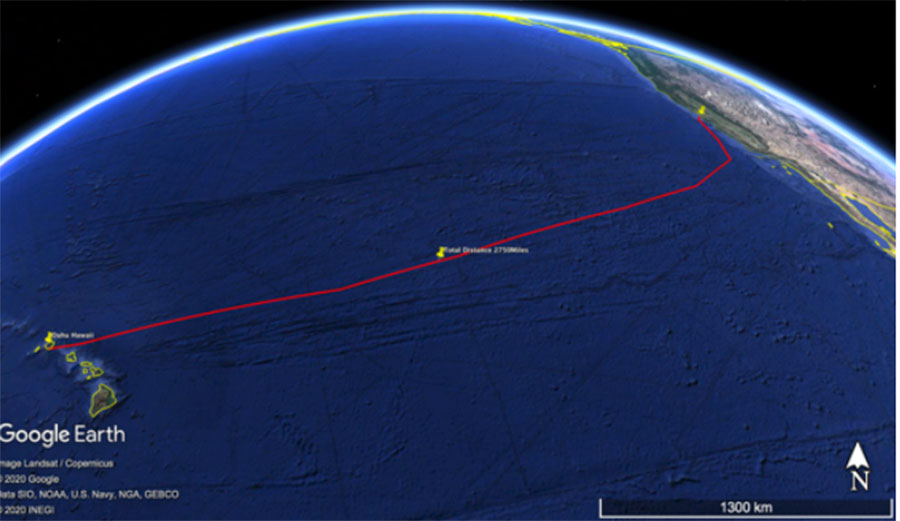

The journey is long, especially if you’re doing it alone on a board with a wing for propulsion. Image: Google Earth/ChrisBertish.com

“I’m working 15-hour days right now,” he says. “The hardest part of the entire journey is just getting the funding to get to the starting line. The adventure is the easy part. That’s the fun part… if you’ve studied the weather conditions and the currents and the trade winds and everything else, then yes, you’re going to have challenging times. Things are going to go wrong. There will be times where you think it’s super hard and you want to give up, but if you can just push through and manage everything, there’s no logical reason why you shouldn’t get to the other side.”

Bertish certainly has had his fair share of challenging times. One, however, stands out from the rest. It happened on his trans-Atlantic crossing, and it’s a tale straight out of a Jules Verne novel. At about 3 a.m., 70 miles offshore and during a violent storm, something snagged onto the parachute anchor he deploys when he’s getting a few minutes of sleep. A parachute anchor is a kind of anchor used when tethering a vessel to the seafloor isn’t possible. Instead of snagging the bottom and holding the craft in place, a parachute anchor uses drag to drastically limit progress. When he awoke, he found he was being pulled at one-and-a-half knots into 45 knots of wind in six to eight-meter seas… which shouldn’t be possible. According to Bertish, the only thing capable of that would be a small whale or a giant squid.

“My steering system had snapped,” he remembered. “A giant squid got caught in my anchor and almost pulled me into the ocean. I had to cut that free.. it was in the middle of the night in the middle of one of the worst storms that I’ve probably ever been in. I was on a craft that really shouldn’t have been out there. I ended up under the craft, and then I had to cut the line to free myself from under it. When I did that, the line went through my finger, down to my bone. By the time it got to daylight, I’d almost had my finger ripped off. My steering system was gone, and I was floating towards the Canary Islands and into one of the busiest shipping lanes that exists on the planet. It was the most hardcore 72-hour period that I’ve ever experienced in my entire life.”

He ended up figuring out how to fix everything that the storm broke. And after that experience, he figured the rest of the trip would be relatively smooth sailing. “If I could get through that,” he said, “I knew I should be able to get through the rest of it.”

Bertish, crossing the Atlantic under his own steam. Photo: Brian Overfeld

I asked him whether, after everything he went through in his trans-Atlantic crossing, he’s at all hesitant to attempt another one that’s thousands of miles long. “For me, the Pacific should be less challenging,” he said. “I know the location of where I’m departing from better. I know the location where I’m arriving. I’ve done the journey in a sailboat across that exact body of water. It makes it a lot easier to swallow and digest and be confident in.”

There are very few people on this planet who have the varied experience that Bertish has under his belt. He’s crossed oceans in sailboats in all sorts of conditions. He knows enormous stretches of ocean like some people know their childhood neighborhoods. That knowledge is what allows him to have the confidence to attempt his Pacific crossing, but it’s not something just anyone could do. It could be argued that there isn’t anyone else in the world so uniquely qualified.

As he did with his Atlantic crossing, the TransPac Wing Project aims to raise money for a variety of organizations. The Atlantic crossing raised enough money to fund close to 1,000 surgeries for children with cleft palates through Operation Smile and feed thousands of kids in impoverished communities through the Lunchbox Fund. The Wing Project will be directly engaged in planting trees through the Thor Heyerdahl Climate Park, sponsoring ocean education outreach programs for more than 1,000 children in disadvantaged communities, donating $5,000 towards shark research, awareness, and protection projects with the Save our Seas Foundation and another $5,000 towards global conservation projects with Conservation International. The Wing Project will also sponsor scholarships for disadvantaged children through the Marine Science Course at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town. He picks which organizations to support with a simple method.

“I do things with people who mirror my visions, values, and core principles,” he said. “People who are aligned with doing good things for other people and for the planet. I’ve got to align with people who align with my values. My cornerstones are people, planet, conservation, education, and sustainability. Those are the five pillars. Each one of our partners aligns with one of those principles.”

Bertish certainly sets lofty goals for himself. He knows that, but he hopes to inspire other people to do the same. He’s right, too — with enough perseverance, willpower, and self-confidence, we can do amazing things. Bertish is a prime example of that. “I want to use the power of the journey to impact the lives of people and be an inspiration,” he said. “I want to be a positive example of what you really can do if you dig deep and bigger than yourself about how you can use a journey to create awareness and a massive positive change. That’s what it’s really about for me.”

Learn more about the TransPac Wing Project on ChrisBertish.com and follow him on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube.