A great white shark from below. Photo: Francesco Califano on Unsplash

Earlier this year, I published an article on a “new technique” to stop bleeding in the event of a shark attack, being pushed by Australian Doctor Nicholas Taylor. Most shark attacks cause injuries to the legs, and so Taylor wanted to generate public awareness that, in the event of a shark bite to the legs, a rescuer can make a fist and push “halfway between the hip and the bits,” to stop blood flow through the femoral artery and potentially save a life. In a lab setting, the technique was able to stop 89.7 percent of blood flow to the leg as opposed to 43.8 percent when using a surf leash as a makeshift tourniquet.

This sounded like a massively helpful technique and something people should know, so I wrote about it, as did plenty of other media outlets. But when I reached out to Surfing Doctors Australia, a group we’ve been in contact with before, my excitement over the technique was met with a “not this snake oil again” attitude.

I just got the chance to speak with Jon Cohen of Surfing Doctors Australia on the subject. Jon was born in Canada but now resides outside of Sydney, a community that knows quite a bit about shark attacks. When I brought up the study with Dr. Cohen, he shared that, in his opinion, the technique is a bit misguided. “I think that they had good intentions. They’re doctors, and so of course they want to help people,” he said. “But I think the assumptions that they made in the article were a step backwards rather than a step forwards.” He believes that there are much better options for stopping bleeding than using your fist, like your knee or even an improvised tourniquet, and that the technique is far from foolproof, and is far less likely to work on the beach than it is in the lab.

Bite marks left after the recent shark attack at Salmon Creek (Calif.). The victim survived, with the help of other surfers who brought him to shore and applied an improvised surf leash tourniquet. Photo: YouTube Screenshot

As for the technique, Dr. Cohen is definitely a believer in the knee technique. “Using your knee is what is commonly taught in a military medical course,” said Dr. Cohen. “The traditional teaching would be to make sure that their junk is out of the way, and to put a knee in that spot and push down with your full body weight. It’s far easier to keep your body weight over your knee than your fist. And that gives you the added advantage of keeping your hands free to dial 911 or setup a real tourniquet with whatever you have on hand.” Dr Cohen seemed skeptical that someone would be able to maintain enough compression with a fist, especially given the possibly agitated nature of someone who’s just been attacked by a shark.

When it comes to the study itself and how it was conducted, Dr. Cohen had some other issues as well. “They were comparing [the fist technique] to a tied off leg rope,” he said, “just a single person trying to pull it in two directions, knowing that it was a study and what the study was trying to prove.” In other words, he believes that the improvised tourniquet they were using for comparison in the study could have been done far better. And furthermore, he’s worried the results of the study might make people think tourniquets aren’t effective.

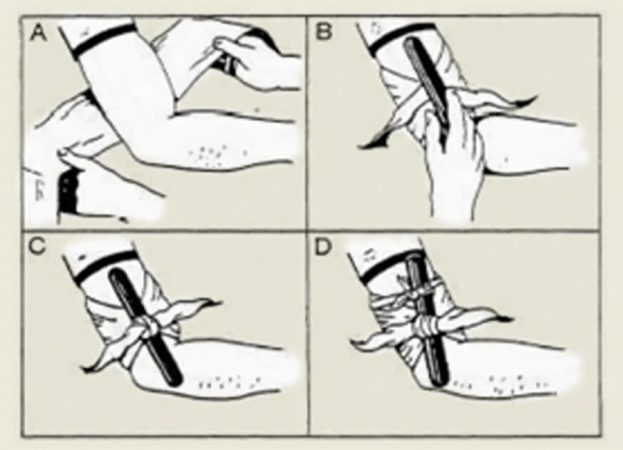

To Dr. Cohen, no matter how much better the knee technique might be than the fist technique, it’s no substitute for a tourniquet. “A tourniquet is the gold standard for stopping bleeding,” he said. “And it is completely possible to make an affective tourniquet with improvised materials.” All you need is something to wrap around the limb – a surf leash, towel or rashguard all work – and something to act as a windlass to tighten the wrap and cut off blood flow. His suggestions included a metal water bottle, spoon, butter knife, even the stiff part of a surf leash where it attaches to the leash cuff.

It’s not an improvised tourniquet without a windlass. Photo: Crisis-medicine.com

In other words, you’ll almost always have something that you can use as a tourniquet close by. All that being said, a true tourniquet will be the most affective, mostly because of how easy it is to use and automatic the actions are to put one on – in traumatic situations like a shark attack happening in the lineup next to you, its the automatic actions that will come to mind first. Which brings up the point of training. It’s far more likely that you will make an actually affective tourniquet with your towel and a butter knife if you’ve been trained to do so.

So a shark attack just happened next to you in the water, what do you do? Dr. Cohen shared that he likes to think about it from the perspective of a few different scenarios. Firstly, if you were to find yourself in the water, off shore with nothing but your hands, Dr. Cohen says “for bleeding from the arms, you can interlace your fingers like a clamshell and clamp down on the brachial artery just above the elbow.” For leg wounds though “you’re going to be really struggling to get enough pressure in the water.” Unless you have a tourniquet. Dr. Cohen told me about the SWAT-T Tourniquet, which you can find on his Calm As website, that is small enough to tuck in the chest zip of a wetsuit without too much discomfort. It’s something he always paddles out with when he’s surfing in a “sharky” location.

SWAT-T stands for Stretch, Wrap, and Tuck Tourniquet. These light and simple to use tourniquets have been in use by the military and emergency professionals for years. Photo: CalmAs.

If an attack happens and you’re able to get the victim to shore, “that’s when you’re able to do the knee-technique,” Dr. Cohen says, but he sees it more like a stop-gap measure until you’re able to get a tourniquet on the victim, or improvise a tourniquet with whatever materials you have on hand.

One thing Dr. Cohen has been working on behind the scenes through his company Calm As, is what he calls “Slam Packs,” a slimmed down medical pack with everything you need to stop major bleeding, and nothing you don’t need to reduce confusion in traumatic scenarios like a shark attack. It comes with two tourniquets, large dressings, and simplified instructions to fall back on. “But to the reader who wants something super cheap they could leave on the beach, a butter knife and towel would be pretty ideal,” he says.

‘Shark’s-eye view’ of a paddling surfer and seal. New research suggests white sharks may struggle to differentiate the two. Photo: Laura Ryan

As a Northern California surfer who could use some peace of mind while I’m out there in the water, I’ll be looking into these SWAT-T tourniquets, as well as tracking down a butter knife and usable towel to leave in my car or on the beach when I’m surfing. It does bear saying that shark attacks are rare, but with two attacks this fall in the Bay Area, one down at Grey Whale Cove and the other up at Salmon Creek, I think it pays to be prepared.

Another note worth mentioning is training. Improvised tourniquets work if done properly, and that’s a big if. Tourniquets should hurt, they need a windlass, and it pays to know how to use one and give it a shot before you’re thrown into a trauma scenario. Here in the U.S., Stop The Bleed is a great program that has been working to train civilians in life-saving techniques. If you plan on spending any time away from civilization, like a remote beach or in the alpine backcountry, taking some sort of first-aid training course is well worth it.

Learn more about sharks in Ocean Ramsey’s Guide to Sharks and Safety.