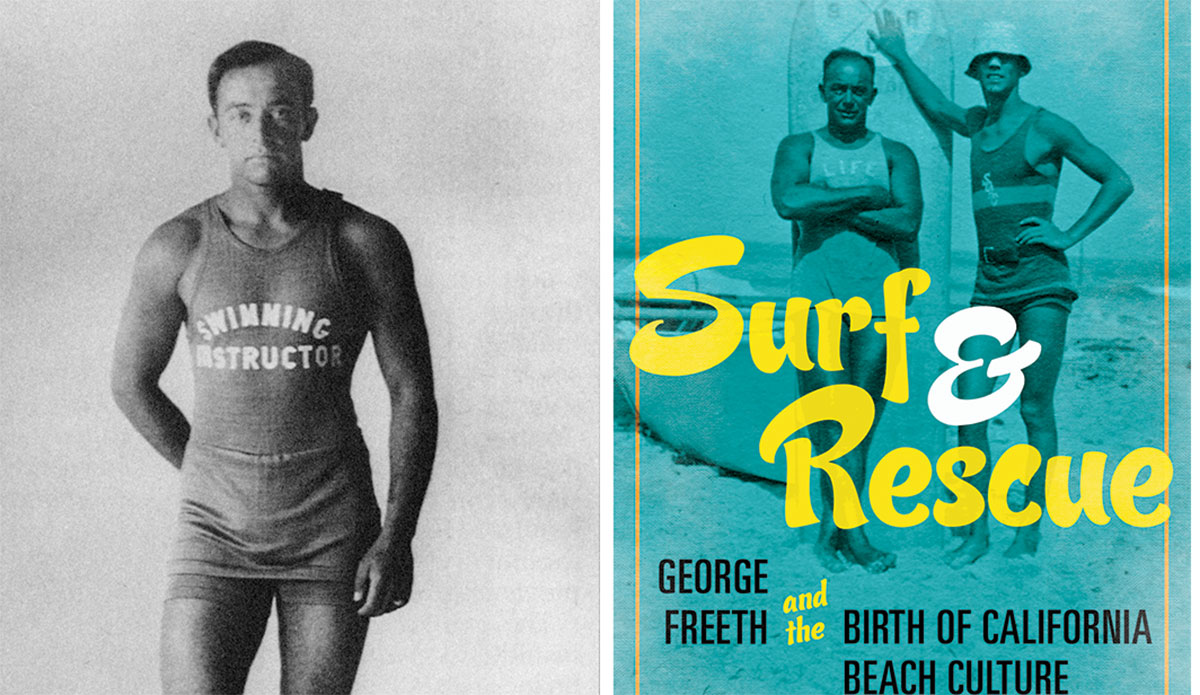

(L:) George Freeth sporting a period bathing suit that highlights one of his major contributions to the development of beach culture in early twentieth-century California: teaching swimming at bathhouses from Los Angeles to San Diego. Photo: Los Angeles County Lifeguard Trust Fund, Witt Family Collection. (R): The cover of Surf and Rescue.

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Surf and Rescue: George Freeth and the Birth of California Beach Culture by Patrick Moser. The book connects the origins of California beach culture with Freeth’s experiences of surfing and lifeguarding, and he’s got a terrific story. Although he died early in the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-1919, George Freeth worked his whole adult life to democratize surfing and give access to the beaches for everyone. The book is available online here.

Beyond the pleasure of competition, Freeth understood the great benefits of water polo for training lifeguards and keeping them in shape. The same techniques that players used to break holds and evade tackles helped them fend off the desperate clutches of drowning swimmers. Experts of the time recommended violent measures for lifeguards to protect themselves—“A vicious bite on the arm or a sudden twist of the thumb or wrist may help you.” In the most drastic cases, a lifeguard should knock the swimmer out: “Should you have the slightest doubt of your ability to handle a struggling man (or woman, for the matter of that) stop their struggling first by a determined blow of your fist on the jaw, just below the ear . . . and then carry them in.”

One of Freeth’s great legacies in California was the young generation of lifeguards that he trained so that they wouldn’t doubt their abilities in the water. Tom Witt, who started competing in diving events when he was seven years old, described his training in Redondo: “I can remember Freeth’s instructions and encouraging words. Freeth taught all us kids confidence, style and fearlessness of the water.” Freeth’s expertise not only saved many lives but he advanced lifeguarding techniques beyond the practice of injuring people in order to save them.

One of Freeth’s early rescues in the Redondo plunge came on a Sunday afternoon in late February 1908. Carl Balmer, an inland visitor, decided to slide down the “chute” even though he didn’t know how to swim. He sank to the bottom and remained there while a group of spectators looked down at him and discussed how they might save him, though nobody attempted to do so. Somebody alerted Freeth.

Freeth was fully dressed—he was just recovering from the mumps. But when he arrived poolside and saw Balmer face down in the deep end, he dove in and pulled him out. It took ten minutes of “hard work” to resuscitate him. Most methods of reviving an unconscious person during this era involved pressing the abdomen to expel water and then moving various parts of the body—arms, legs, even the tongue—to encourage reanimation. The idea of introducing air into the lungs had not yet become standard, but stories of victims being revived after three or four hours encouraged lifeguards to keep working over a person. In the summer of 1912 Freeth himself revived a drowning victim, A. P. Broadwell, after laboring for nearly three hours.

The next report of Freeth saving a swimmer came in mid-June from Venice. It’s the first indication that he’d left Henry Huntington’s employ in Redondo and was now working for Abbot Kinney again. The swimmer, Fred Ravilla, had ignored warnings and stroked out beyond the safety line—a fixed rope between the shore and surf that swimmers could hang onto. So Freeth had to go get him. He worked over Ravilla for half an hour before the man regained consciousness.

Lucky for Ravilla that Freeth had decided, within ten days of winning the water polo championship for Redondo, to move back to Venice. Freeth had probably been drawn back by the opening of Abbot Kinney’s new $100,000 bathhouse, situated on the beach boardwalk. It was a two-story, Spanish-Renaissance-style building that fit thousands of people in the pool and balcony. Redondo had Huntington’s grand dancing pavilion, but the old bathhouse would have felt shabby compared to Kinney’s fancy plunge, with its fifty-foot domed roof, its great windows facing the beach, its grand columns and electric light bulbs decorating the structure. It probably gave Kinney some satisfaction too—stealing Freeth from Huntington. Kinney always wanted the best for his resort, and Freeth had proven himself the top lifeguard, surfer, and water polo player in Los Angeles. Twenty thousand people were estimated to have attended opening-day festivities on June 21, and Freeth, who always enjoyed performing, would have relished being a star attraction.

And he was. You couldn’t have missed him if you’d tried. Freeth opened the water sports that day with a surfing exhibition. “The tide was running high,” The Los Angeles Times reported, “and the white-crested waves fairly raced shoreward.” He then swam the 50-yard freestyle against Frank Holborow (and lost). He put on a diving exhibition with Jake Cox from the rafters of the new plunge. The program ended with a water polo match between Venice and Frank Holborow’s Bimini Baths, with Freeth’s team winning two to one.

To top off his day, Freeth helped rescue a swimmer in the plunge. Surfing, swimming, diving, water polo, lifesaving—all in one day. Could Freeth have been any more in his element?

Venice turned out to be a good move for Freeth, setting him up for the single most heroic day of his life.