On June 8th, 1708, a Spanish galleon called the San José sank to the bottom of the ocean. It carried some 600 sailors and a haul that, in today’s dollars, would be worth up to $17 billion dollars. How do we know the value of the treasure it carried? Because, after 300 years of speculation, a submersible robot called the Remus 6000 found it.

The San José was part of a large fleet of Spanish vessels tasked with crossing the Atlantic to the newly discovered Americas and returning with as much treasure as they could carry. A few hundred years before they set out, Columbus took his first voyage across the Atlantic looking for India. As a side note, although Columbus has long been hailed as the man who discovered the Americas and proved the earth was round, he was actually more of a bumbling, stubborn idiot who accidentally ran into Hispaniola, mistakenly believed he’d hit India, then bounced all over the place killing everyone and stealing everything he possibly could (here’s a cute little cartoon that explains it).

After enormous amounts of silver were found Potosí in Peru Alto—which is present-day Bolivia—back in the mid-1500s, it fueled a silver rush that turned Peru into “Spain’s great treasure house in South America.” The Spanish fleet that the San José was a big one and most of the ships were well equipped to fight off pirates or other nations’ fleets looking to steal their ill-gotten gains. The San José sailed under the protection of a fleet of warships, but for some reason, the escorts ships were delayed for that particular voyage back to Spain. Fleet commander Admiral José Fernandez de Santillan decided to go at it alone, possibly because the San José had 62 bronze cannons aboard, all intricately designed with engraved dolphins and built to protect the ship. With all those cannons, however, comes a whole lot of gunpowder, which would prove to be the fatal stroke. On that fateful day during the War of the Spanish Succession, the San José ran into a British squadron sailing under Admiral Sir Charles Wager and waged a ferocious fight that would become known as Wager’s Action. It ended with the gunpowder stores aboard the Spanish vessel exploding, breaking the ship apart and sending it down to the bottom of the sea. It was loaded with silver, jewels, and gold taken from Peruvian mines, and the rumor of the massive treasure it carried with it earned it the nickname of “the Holy Grail of Shipwrecks” and was fodder for centuries of searching.

Enter the Remus 6000. Operated by the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, it uses sonar to poke around at the bottom of the ocean, reading the pings it receives back, similar to how a bat locates prey. Different sounds indicate different densities of objects on the seafloor, and when it strikes something of note, the Remus 6000 snaps a few images to send back to researchers.

As a part of a Colombian expedition using a Navy research called the ARC Malpelo, it searched the Caribbean Sea’s Baru Peninsula. On November 27th, 2015, they found what they were looking for. “During that November expedition, we got the first indications of the find from side scan sonar images of the wreck,” Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution expedition leader Mike Purcell told The Smithsonian. “From those images, we could see strong sonar signal returns, so we sent REMUS back down for a closer look to collect camera images.”

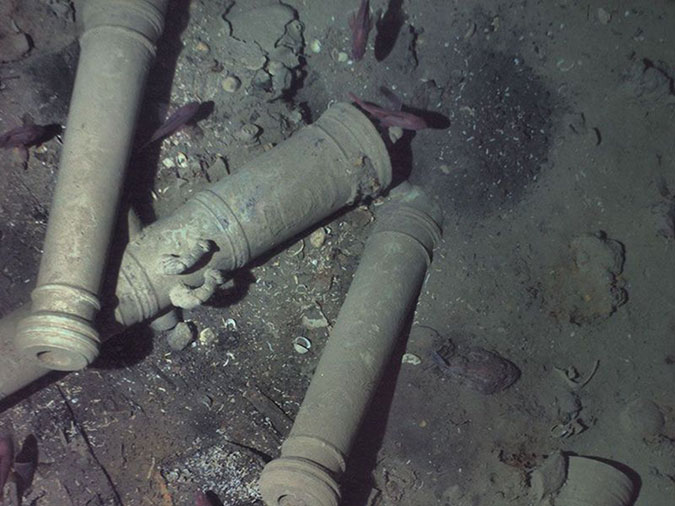

The San José, after 300 years, was almost entirely covered in mud, but enough of it protruded from the sediment that researchers were able to confirm its identity. “The wreck was partially sediment-covered, but with the camera images from the lower altitude missions, we were able to see new details in the wreckage and the resolution was good enough to make out the decorative carving on the cannons,” said Purcell in a press release. “MAC’s lead marine archaeologist, Roger Dooley, interpreted the images and confirmed that the San José had finally been found.”

In November 2015, the MAC survey team and WHOI researchers returned to Colombian waters for a second search effort. Side scan sonar images gave the crew the first indications of the find from of the wreck. To confirm the wreck’s identity, REMUS descended to just 30 feet above the wreck where it was able to capture photos of a key distinguishing feature of the San José—its cannons. (REMUS image, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Now, however, the wreckage has become the source of a somewhat heated debate: who owns the treasure? Both Spain and Colombia lay claim to it. Spain says it’s theirs because they owned the ship, and Colombia says it’s theirs because it was found in their waters.

However the dispute turns out, the discovery of the San José will go down in history as one of the world’s greatest maritime finds, and not only for the treasure. “The San José discovery carries considerable cultural and historical significance for the Colombian government and people,” said WHOI in the press release, “because of the ship’s treasure of cultural and historical artifacts and the clues they may provide about Europe’s economic, social, and political climate in the early 18th century.”