The evolution of ski movies.

This January, I sat on my couch and edited together some GoPro footage from a powder day over Christmas break. Between rummaging through clips and picking songs — as well as pausing every now and again to reminisce on how epic that day was — creating the edit took all night. I really wanted the three, maybe four people who would watch it to think it was awesome. I then posted it on Vimeo and boom, I had made a ski movie for all the world to see.

Producing and distributing a ski movie used to be much, much harder; the industry has come a long way since its inception. The technology, content, and means of distribution have all undergone major advancements since Warren Miller and other pioneers began traveling around the country filming the on-hill endeavors of their friends.

What began as a few men traveling around the country, displaying the sport through projectors in local theaters, has become a vast industry, spanning from DVD distribution to online marketing. The movies and the sport have progressed in tandem with each other: when freeskiing was forming a new identity, the films changed in order to convey it. Advancements on the hill led to a new style of skiing and a new type of movie, which emerged through new audio and video technology. The sport has undergone many changes since the Warren Miller era, and the corresponding medium through which that progression is displayed has evolved as well.

Photo: Amazon

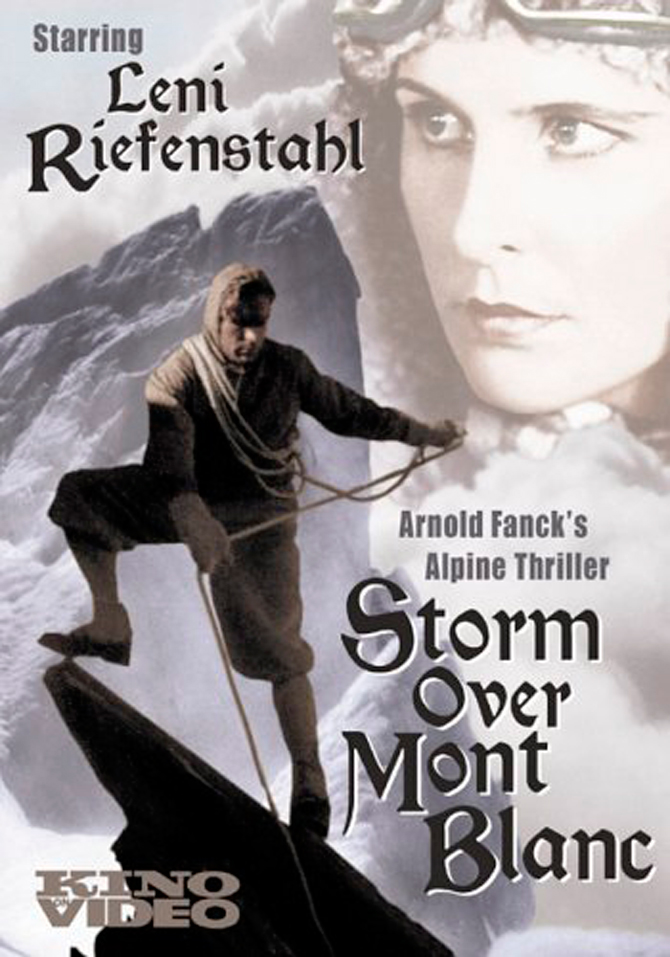

Even before stalwarts such as Warren Miller, there was Dr. Arnold Fanck, the godfather of the art form. In the 1930s, the German filmmaker’s fictional black-and-white movies centered on characters living in the mountains. The storylines featured, among other mountaineering exploits, a protagonist skiing away from villainous characters.

His 1930 film Storm over Mont Blanc took place in Chamonix, France. (Yes, Chamonix has been a staple of ski movies since the inception of ski movies.) Fanck elected a young German dancer, Leni Riefenstahl to act in many of his films.

The successes of his films weren’t limited to those who gravitated towards mountains. They reached audiences across the country — this was an era when all films, no matter the subject, we’re a big deal… it just so happened that one of the earliest pioneers of filmmaking had a deep interest in the outdoors. Years later, Adolf Hitler would even go on to handpick Riefensthal to oversee the filming of the 1936 Olympics, a testament to the pervasive reverence for Fanck’s influence. About a decade after, an Austrian ski instructor named Otto Lang brought these films to the United States; and around the same time an avid skier named John Jay began making his own films. A wide-eyed visionary named Warren Miller soon followed.

Photo: Snowbrains.com

Over a 50-year career, Warren Miller produced a feature film every single year. Of all the ski filmmakers from his era, his name is the far-and-away the one that is most immediately recognizable to those outside of the ski world.

Given the resources and mediums/formats available to him at the time, this recognition is rather impressive. Back in the day, the only way to watch one of Miller’s ski movies was to go to one of the theater stops along the cross-country tour. The movie would be projected while the soundtrack played separately on a record player. Miller would then narrate the movie. The films would be humorous and awe-inspiring, ultimately stimulating your sense of adventure.

Thus, Miller and his crew epitomized ski movies for decades.

Any Snow Any Mountain (1971) — which starred Jim McConkey (Shane’s father) — took viewers from Squaw Valley to Whistler to Japan, showcasing monoskiing and the birth of airborne skiing. Featuring progression of this ilk, Miller’s films highlighted the changes of the sport. They tended not to focus on specific athletes, but instead specific locations and different cultures. Ultimately, one of his proteges added trippy special effects, expanding the medium’s artistic boundaries. Shortly thereafter, another filmmaker in Dick Barrymore integrated storylines into his movies.

Back then, there weren’t pools of professional extreme skiers that movie companies would recruit from. The skiers in these films had day jobs, or at least competed in some facet of skiing, ranging from racing to ballet… that’s right, ski ballet used to be a thing.

One ballerino in particular, Greg Stump, caught Dick Barrymore’s eye. Barrymore invited Greg on a trip that would produce footage for his next film. The teenage Stump observed Barrymore do everything, from filming to making travel arrangements. His efforts both impressed and inspired Stump, who would eventually come to the conclusion that he was capable of doing the same.

Hailing from Vermont, Greg Stump had a solid crew of East-Coast skiers with which to fill of the roster of a ski movie. As he sharpened his filmmaking skills, his network of available athletes expanded.

Then came 1987, when Stump released his iconic film The Blizzard of Aahhh’s. It was a game-changer. The stars of the movie, Scot Schmidt and Glen Plake, became living legends overnight, and an appearance on the Today Show brought not just the sport but the counterculture spirit of freeskiing into the mainstream.

They were polar opposite personalities: Plake was brash, sported a mohawk, and had to remain in France after filming because of outstanding warrants in the U.S.; Schmidt was soft-spoken, polite, and instantly became known as the one of the most technically sound backcountry skiers in the world.

Photo: OrangePow.com

All of a sudden, a new type of ski movie was born. Stump used music that was popular at the time, thanks to some technological advances in the music industry. Even Miller admits he may have stuck with symphonic music for too long. Like anything else, luck played a factor — the band that Stump approached to provide the soundtrack for the film we’re avid skiers and big fans of European ski movies, descendants of Dr. Funke’s films. That passion for skiing played a role in encouraging the band to give Stump access to the music… for free.

Prior to the release of the film, Tony Hawk famously appeared in a Super Bowl commercial riding a loop. Action sports we’re beginning to break into the mainstream.

Remember, this was the late eighties. Reagan conservatism was in full-force; Blizzard of Aahhh’s thrust freeskiing into the same category as Dogtown skateboarding and surf culture. Skiing was beginning to shed an image defined by Aspen vacationers and strict powder 8-turns. It was starting to embody one word: extreme. Miller had first ventured into displaying extreme skiing in 1984, but Stump’s signature film is known as a major factor in that perception shift. And it was also responsible for inspiring a new generation of skiers.

Shane McConkey was attending CU Boulder when he first watched Blizzard of Aahhh’s. The ex-racer bought into the style of skiing exposed in the movie. Extreme skiing inspired a new type of athlete, and a new type of ski film.

In 1993, Matchstick Productions (MSP) released its first movie. Their secret formula: jaw-dropping action set to rad music. Pretty simple, right? Well, It worked. The company, founded by Steve Winter and Murray Wais, is the most award-winning ski movie company ever. In the early nineties, ski filmmakers were still following variations of the models pioneered by Warren Miller and Greg Stump films. Other action sports, however, we’re portrayed by their respective filmmakers in a different way. They used a formula that MSP would bring into the ski world.

Wais credits Standard Films, especially their movie Totally Board (1991), and Mack Dawg Productions with having a big influence on his and Steve Winter’s approach to producing a new type of ski movie.

“Those times we’re a lot different,” says Wais, talking about the era during which he founded MSP. “There wasn’t a lot of skiing content.”

He and Winter decided to “just [focus] on the action. Our movies just focused on skiing and action.” As a result, he and the MSP team “would be twenty years the youngest guys” at ski movie industry meetings.

If you haven’t seen a Warren Miller, John Jay, or Dick Barrymore film, it’s hard to imagine how much of a deviation the format championed by MSP truly was. Soul Sessions and Epic Impressions (1993), their first film, features the same format that appears in today’s conventional ski movie.

MSP really hit their stride in 2000, with Ski Movie, which won “Movie of the Year” from both Powder magazine and Freeze magazine.

As mentioned earlier, Warren Miller’s films showcased the diverse culture of skiing; the different ways in which people with a love for the sport express that passion. His movies are more documentary than music video. To be fair, when he was the most iconic member of the ski filmmaker corps, there was not as much action to show. Not as many skiers were pursuing the tricks, maneuvers, or hucks that could captivate an audience in a six-second time frame.

MSP rose to prominence when the sport was starting to move in the direction of a more gnarly or technically difficult direction. As is typical with the evolution of the ski industry, the movies played a role in that development as well.

Beginning in 1995 with the The Tribe, Shane McConkey was both a mainstay in MSP films and one of the top athletes in the freeride tour. Their collaborations helped elevate the popularity of extreme skiing. McConkey was also behind major innovations in the sport. He helped pioneer using fatter skis in powder.

In one MSP film, he slides down the face of a backcountry slope on old-school waterskis, proving that such equipment could be useful, and putting his stamp on a new approach to the sport. The concept of a “rocker” ski was born out of those types of experiments. If it wasn’t for Shane, we might still be jump-turning in perfect powder. That style seems like blasphemy now. McConkey’s progressive attitude was changing the sport, and MSP was one of the mediums in which he promoted those developments.

The sport was undergoing major changes and so was the media that documented it. In 1995, Johnny Decesare founded Poor Boyz Productions. One year later, Teton Gravity Research appeared on the scene. These award-winning companies used a formula more akin to MSP than Warren Miller. That style effectively laid the foundation for much of you what you see today, with one other major change to come — the internet and social media.

Nowadays, you don’t have to go to the website of a ski movie company and order their new movie. You can instead buy them on iTunes, Vimeo, or stream them for free. In fact, there is so much ski media available that I often wonder if that level of accessibility hurt the businesses that popularized the one-off film release. For instance, since you can watch edits of your favorite skiers year around, maybe fans are not as inclined to purchase the movies, whether in DVD form or online. Quite the contrary, according to Wais, social media has “widened [their] distribution channels… we sell more movies than ever.”

Nonetheless, some film companies have made the move away from once-a-year features and towards a web series. That trend has been reflected in the work of companies that manufacture products related to skiing, such as Solomon Freeski TV. Releasing media online is a keen way to market your product, especially when that media looks and sounds like a ski movie; and movie watchers prefer digital purchasing rather than waiting for the physical copy to arrive. The web series movement represents filmmakers adapting to that trend.

However, the ski movie world might be immune to declines in DVD sales because it feeds off a cult following. Releasing trailers online has also become a major part of the industry. When trailers start popping up in late-summer/early-fall, that influx of media helps make up for an absence of ski videos during the previous months. People will always watch the ski movies produced by the big name companies every year, but a spectacular trailer can be the difference for a lesser-known production team.

Perhaps the biggest change to come with the digital movement is control, namely control by athletes over their own content. Take Cody Townsend, whose one-minute video of an unbelievable line went viral last year. The accomplished professional skier spoke about his motivation to create his own movie this year, instead of starring in someone else’s. “I felt like I had done everything,” Cody says. “I ran out of dreams.”

He’s starred in MSP movies, being featured “in the upper echelon of big mountain action.” It was time to do it himself. His movie will feature more of a narrative than the average content of today’s movies.

Talking about the state of the industry, Cody said “the typical ski movie format, without a story, relies on one-up-man-ship. You have to visually wow people every year.” Cody obviously has the skills to one-up skiing’s best athletes every year, but let that be a lesson to the up-and-coming filmmakers that don’t have the budget to one-up the competition visually — narratively inclined ski movies are trending up.

Cody’s decision to make his own movie underscores another big shift in the art form. Making a ski movie is much cheaper and easier than it used to be; the advent of digital filming and editing changed the game.

Until 2003, MSP used a 16-millimeter camera and edited their movies the old fashioned way. Keep in mind, a 16-mm camera is what John Jay used way back in the 1950s; but then MSP began using Red cameras, and the filmmaking and post-production process became much easier.

When Stump was filming his The Blizzard of Aaahh’s, they would have to wait two weeks before seeing any of the footage. They would send out the reel and wait for it to be processed and sent back. Today, filmmakers can watch their footage right after skiing, shortening and cheapening the post-production process. Anyone with a smart phone or a GoPro can film, edit, and distribute their own movie for free — except of the price of lift tickets, of course.

Short edits can stimulate a viewer’s love for skiing just as successfully as feature films. And now that the whole world logs onto the Internet everyday, edits generally have more of an impact on how often freeskiing appears in the mainstream.

Case in point: Candide’s “One of Those Days” videos, and Cody Townsend’s aforementioned line as filmed by Matchstick (by Cody’s helmet). The GoPro has forever changed amateur video creation. Professional skiers have been strapping cameras to their helmets for decades, despite the bulkiness of a 16mm. Still, that camera angle was reserved for professionally made videos. Now anybody can provide a first-person look into his or her run, whether it’s on the bunny slope or in the backcountry. GoPros have also pushed a new trend in the editing of ski videos. Some of the best POV edits seen nowadays involve one distinctive feature — no music. The sounds of snow and wind whishing by a skier add to the first-person effect provided by the camera angle. Hearing Candide absorb moguls as he straight-lines towards a booter enhances the intensity of the moment. Basically, if the line is gnarly enough, music is not only unnecessary, but may even detract from the “wow” factor.

In order to film Blizzard of Aahhh’s, Greg Stump and his athletes traveled to Chamonix, France. At the time, filming that type of skiing at U.S. ski resorts was difficult because of liability issues. Such is not the case anymore, but many ski films still feature international and remote locations. When Teton Gravity Research emerged on the scene, they brought with them footage of the Alaskan backcountry. According to Greg Stump, TGR’s showcasing of those mountains promoted Alaska as the “North Shore of skiing.”

As the ski movie industry has grown, so has the budgets of the companies. I would be remiss to not mention the increased opportunities afforded the ever-influential talents of female skiers who also appear on screen, such as Michelle Parker, Angel Collinson, Ingrid Backstrom, and Sierra Quitiquit, just to name a few. Or the increased presence of urban skiing, for that matter. In the annals of ski films, urban skiing is a relatively new feature. Still, it appears in nearly every movie and in some cases is the entire focus. The level of progression in urban environments has mirrored that of traditional freeskiing. These segments always prove gritty, but they showcase a passion for skiing that is endearing inspiring.

Further opportunities lie in foreign travel. The movie that tipped my obsession with ski films, Matchstick’s Seven Sunny Days (2007), showcased Mark Abma and other pros skiing in India. More and more, ski films include segments in obscure places. There have been powder segments in Japan and urban segments in Helsinki, Finland. For filmmakers trying to distinguish their work from the rest of the year’s batch, including segments based in uncommon ski destinations represents a solution.

Speaking of Japan, prepare to see a lot of sake in this year’s collection of films. The mid-winter drought in the Rockies forced the snow crazies to head east…way east. Climate change is affecting all of our ski seasons, whether you are a professional or not. For pro skiers, climate change impacts their seasons by forcing them to relocate in search of fresh snow and this past year’s mass migration to Japan perfectly exemplifies this phenomenon. Weather plays a big role in determining some of the locations that appear in ski movies. As climate change leads to increasingly erratic weather patterns, ski movie companies have been forced to follow the snow. That search seems to be impacting the storyline and regions featured in some upcoming films, and will certainly continue to play that role.

Photo: Courtesy of MSP

Still, one specific quality of the ski industry creates an incentive to stick with the one-off feature formula — it’s a seasonal sport. You film during the winter, edit during the summer, and release in the fall when everyone is jonesing to start skiing again. Releasing video segments throughout the year fails to tap into that concentrated craving.

Not surprisingly, Cody says his friends involved in other action-sports are jealous of that timeline. The annual fall releases are a marketer’s dream. Sports like skateboarding and surfing are not limited by the seasons. Those filmmakers are not restricted in their production timeline like the ski industry. Outside of a few South American countries that provide only one type of landscape, filming ski movies largely take place in the Northern Hemisphere.

Ultimately, despite advancements, the ski movie premiere a la Warren Miller has not suffered. In fact, social media and the internet has enhanced the appeal of skiing to a larger audience, attracting fans to those premieres who may not have followed skiing if it wasn’t for the availability of videos online. And if there is still any doubt that these premieres are here to stay for at least the foreseeable future, Townsend offered one more convincing reason: “people love to get drunk and yell at a ski movie.” Sounds like a timeless to ritual to me.