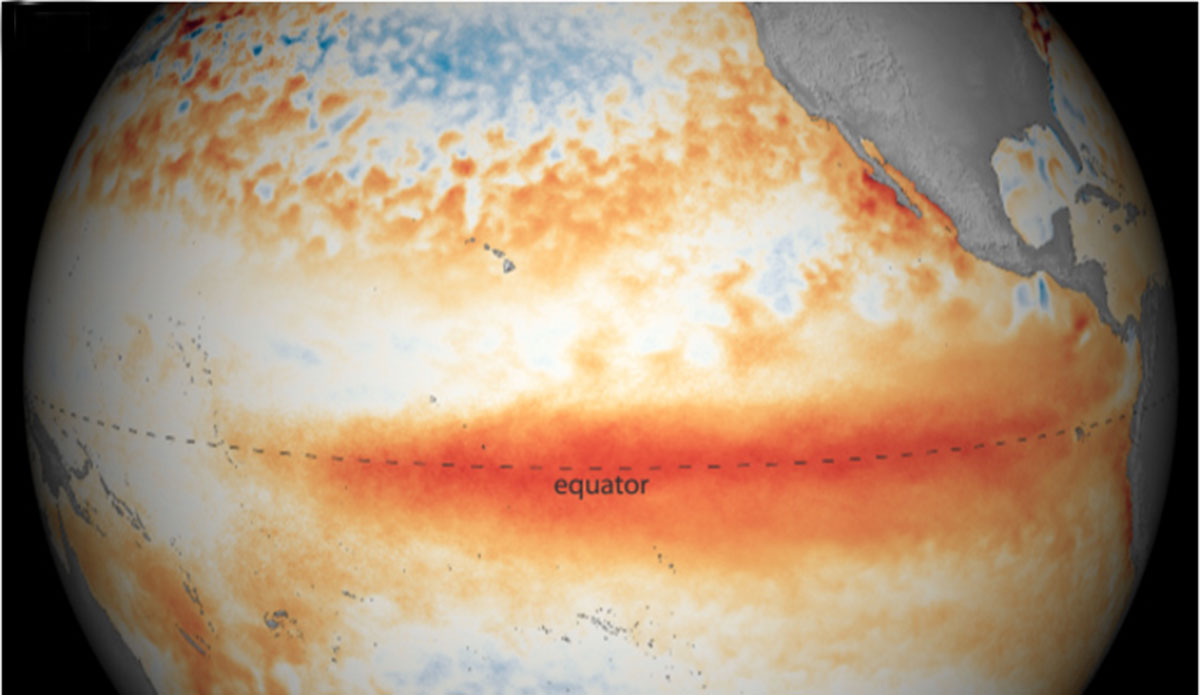

Climate models show a good chance of a strong El Niño year. Image: NOAA

Researchers are keeping a close eye on ocean patterns this year, as climate models around the world are indicating a possible “super El Niño” event. It would come after three consecutive La Niña years, a rare phenomenon called a “triple-dip.”

El Niño events, as you likely are aware, occur when the surface waters of the the eastern Pacific Ocean are warmer than normal. When they do occur, they spur weather events that can have catastrophic consequences — and as El Niños get stronger with a little help from human-caused climate change, those weather events are getting harder and harder to deal with.

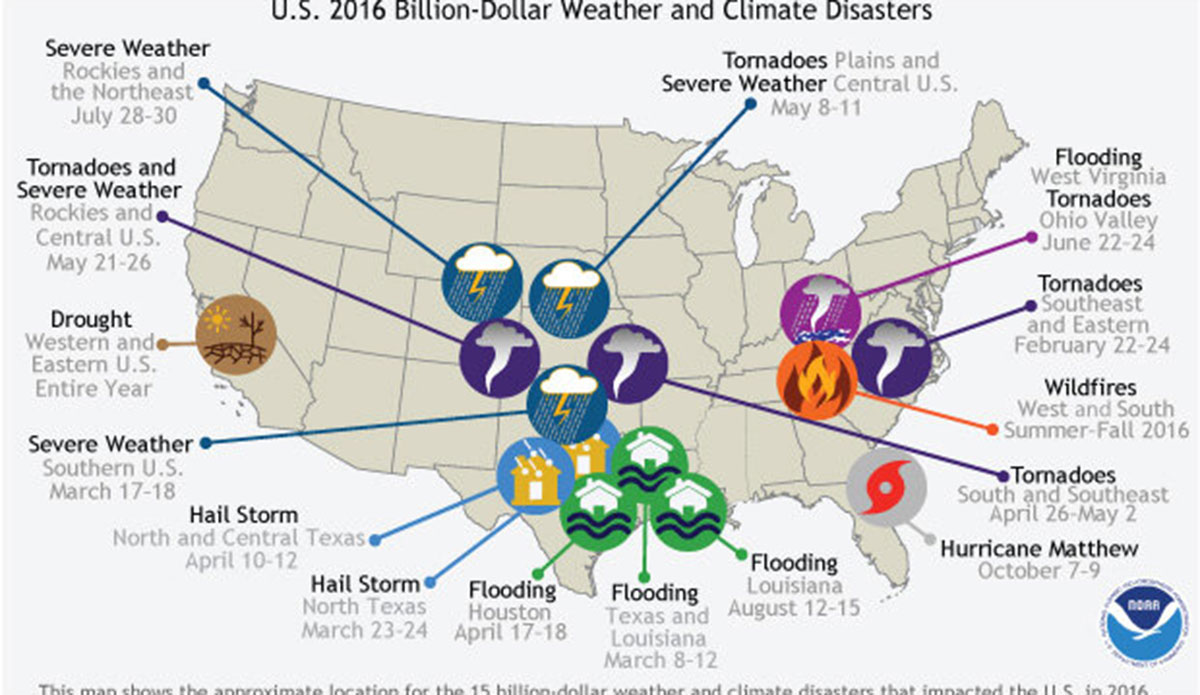

The last time there was an extreme El Niño was in 2016, when global average temperatures broke records. That year, if you’ll cast your mind back to a pre-pandemic time, wasn’t so great in terms of devastating weather. According to Climate.gov, an arm of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “The year 2016 was an unusual year, as there were 15 weather and climate events with losses exceeding $1 billion each across the United States. These events included drought, wildfire, four inland flood events, eight severe storm events, and a tropical cyclone event. Cumulatively, these 15 events led to 138 fatalities and caused $46.0 billion in total, direct costs. The 2016 total was the second highest annual number of U.S. billion-dollar disasters, behind the 16 events that occurred in 2011.”

The location and type of the 15 weather and climate disasters in 2016 with losses exceeding $1 billion dollars. Image: NOAA NCEI//Climate.gov.

In an update from Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology, the public was informed that out of seven climate models surveyed, all of them showed that by August, sea surface temperatures will pass the El Niño threshold. In order to meet that threshold, temperatures must be at least .8C above the long term average. To be classified as an extreme El Niño, temperatures must be at least 2C higher.

There’s still plenty of time before August, though, so researchers did warn against taking the climate models as gospel. They said that “that forecasts were much less reliable during the southern hemisphere autumn and outlooks should be ‘viewed with some caution.’”

According to senior research scientist at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), El Niños typically come about once every four years or so.

“We’re due one,” NOAA’s Dr. Mike McPhaden said. “However, the magnitude of the predicted El Niños shows a very large spread, everything from blockbuster to wimp.”

While it’s normal for regular El Niño events to occur every few years, it’s abnormal to have extreme ones so close together. Those large events are more of a once every 15-20 years thing. Since the last big one was in 2015-2016, another one this year would be “very unusual,” according to Dr. McPhaden.

“The really big ones reverberate all over the planet with extreme droughts, floods, heatwaves, and storms,” Dr. McPhaden warned. “If it happens, we’ll need to buckle up. It could also fizzle out. We should be watchful and prepared either way.”

Editor’s Note: Welcome to The Inertia. Find out more about us and explore some of our archives here.