Skimming oil in the Gulf of Mexico during the Deepwater Horizon spill, May 29, 2010.

Image: NOAA , CC BY

The Trump Administration is proposing to ease regulations that were adopted to make offshore oil and gas drilling operations safer after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. This event was the worst oil spill in U.S. history. Eleven workers died in the explosion and sinking of the oil rig, and more than 4 million barrels of oil were released into the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists have estimated that the spill caused more than US$17 billion in damages to natural resources.

I served on the bipartisan National Commission that investigated the causes of this epic blowout. We spent six months assessing what went wrong on the Deepwater Horizon and the effectiveness of the spill response, conducting our own investigations and hearing testimony from dozens of expert witnesses.

Our panel concluded that the immediate cause of the blowout was a series of identifiable mistakes by BP, the company drilling the well; Halliburton, which cemented the well; and Transocean, the drillship operator. We wrote that these mistakes revealed “such systematic failures in risk management that they place in doubt the safety culture of the entire industry.” The root causes for these mistakes included regulatory failures.

Now, however, the Trump administration wants to increase domestic production by “reducing the regulatory burden on industry.” In my view, such a shift will put workers and the environment at risk, and ignores the painful lessons of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. The administration has just proposed opening virtually all U.S. waters to offshore drilling, which makes it all the more urgent to assess whether it is prepared to regulate this industry effectively.

Separating regulation and promotion

During our commission’s review of the BP spill, I visited the Gulf office of the Minerals Management Service in September 2010. This Interior Department agency was responsible for “expeditious and orderly development of offshore resources,” including protection of human safety and the environment.

The most prominent feature in the windowless conference room was a large chart that showed revenue growth from oil and gas leasing and production in the Gulf of Mexico. It was a point of pride for MMS officials that their agency was the nation’s second-largest generator of revenue, exceeded only by the Internal Revenue Service.

We ultimately concluded that an inherent conflict existed within MMS between pressures to increase production and maximize revenues on one hand, and the agency’s safety and environmental protection functions on the other. In our report, we observed that MMS regulations were “inadequate to address the risks of deepwater drilling,” and that the agency had ceded control over many crucial aspects of drilling operations to industry.

In response, we recommended creating a new independent agency with enforcement authority within Interior to oversee all aspects of offshore drilling safety, and the structural and operational integrity of all offshore energy production facilities. Then-Secretary Ken Salazar completed the separation of the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement from MMS in October 2011.

Officials at this new agency reviewed multiple investigations and studies of the BP spill and offshore drilling safety issues, including several by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. They also consulted extensively with the industry to develop a revised a Safety and Environmental Management System and other regulations.

In April 2016, BSEE issued a new well control rule that required standards for design operation and testing of blowout preventers, real-time monitoring and safe drilling pressure margins. Prior to the Deepwater Horizon disaster, the oil industry had effectively blocked adoption of such regulations for years.

About-face under Trump

President Trump’s March 28, 2017, executive order instructing agencies to reduce undue burdens on domestic energy production signaled a change of course. The American Petroleum Institute and other industry organizations have lobbied hard to rescind or modify the new offshore drilling regulations, calling them impractical and burdensome.

In April 2017, Trump’s Interior Secretary, Ryan Zinke, appointed Louisiana politician Scott Angelle to lead BSEE. Unlike his predecessors – two retired Coast Guard admirals – Angelle lacks any experience in maritime safety. In July 2010 as interim Lieutenant Governor, Angelle organized a rally in Lafayette, Louisiana, against the Obama administration’s moratorium on deepwater drilling operations after the BP spill, leading chants of “Lift the ban!”

Even now, Angelle asserts there was no evidence of systemic problems in offshore drilling regulation at the time of the spill. This view contradicts not only our commission’s findings, but also reviews by the U.S. Chemical Safety Board and a joint investigation by the U.S. Coast Guard and the Interior Department.

Oiled Kemp’s Ridley turtle captured June 1, 2010, during the BP spill. The turtle was cleaned, provided veterinary care and taken to the Audubon Aquarium.

NOAA, CC BY

Fewer inspections and looser oversight

On December 28, 2017, BSEE formally proposed changes in production safety systems. As evidenced by multiple references within these proposed rules, they generally rely on standards developed by the American Petroleum Institute rather than government requirements.

One change would eliminate BSEE certification of third-party inspectors for critical equipment, such as blowout preventers. The Chemical Safety Board’s investigation of the BP spill found that the Deepwater Horizon’s blowout preventer had not been tested and was miswired. It recommended that BSEE should certify third-party inspectors for such critical equipment.

Another proposal would relax requirements for onshore remote monitoring of drilling. While serving on the presidential commission in 2010, I visited Shell’s operation in New Orleans that remotely monitored the company’s offshore drilling activities. This site operated on a 24-7 basis, ever ready to provide assistance, but not all companies met this standard. BP’s counterpart operation in Houston was used only for daily meetings prior to the Deepwater Horizon spill. Consequently, its drillers offshore urgently struggled to get assistance prior to the blowout via cellphones.

On December 7, 2017, BSEE ordered the National Academies to stop work on a study that the agency had commissioned on improving its inspection program. This was the most recent in a series of studies and was to include recommendations on the appropriate role of independent third parties and remote monitoring.

Minor savings, major risk

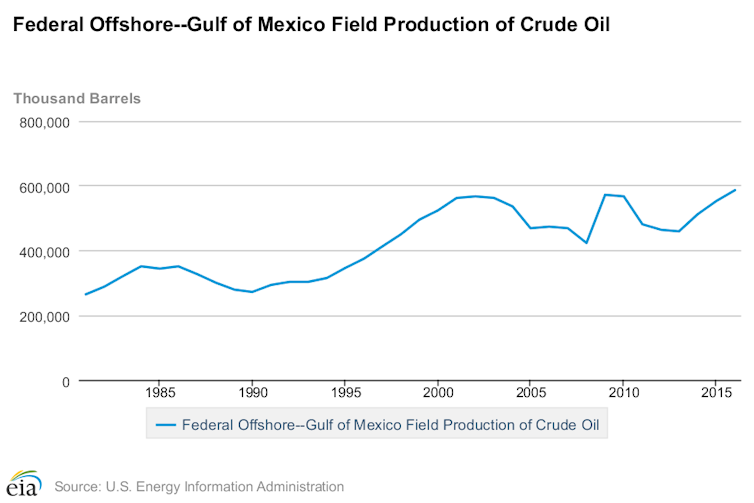

BSEE estimates that its proposals to change production safety rules could save the industry at least $228 million in compliance costs over 10 years. This is a modest sum considering that offshore oil production has averaged more than 500 million barrels yearly over the past decade. Even with oil prices around $60 per barrel, this means oil companies are earning more than $30 billion annually. Industry decisions about offshore production are driven by fluctuations in the price of crude oil and booming production of onshore shale oil, not by the costs of safety regulations.

BSEE’s projected savings are also trivial compared to the $60 billion in costs that BP has incurred because of its role in the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Since then explosions, deaths, injuries and leaks in the oil industry have continued to occur mainly from production facilities. On-the-job fatalities are higher in oil and gas extraction than any other U.S. industry.

![]() Some aspects of the Trump administration’s proposed regulatory changes might achieve greater effectiveness and efficiency in safety procedures, but it is not at all clear that what Angelle describes as a “paradigm shift” will maintain “a high bar for safety and environmental sustainability,” as he claims. Instead, it looks more like a shift back to the old days of over-relying on industry practices and preferences.

Some aspects of the Trump administration’s proposed regulatory changes might achieve greater effectiveness and efficiency in safety procedures, but it is not at all clear that what Angelle describes as a “paradigm shift” will maintain “a high bar for safety and environmental sustainability,” as he claims. Instead, it looks more like a shift back to the old days of over-relying on industry practices and preferences.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.