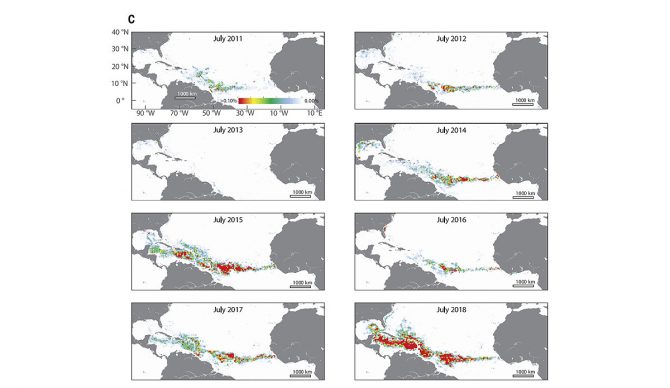

Dramatic increases in sargassum seem to begin in 2011. Photo: ‘Science’

If you were tasked with guessing how big the world’s largest patch of seaweed is, “the width of the Atlantic Ocean” probably wouldn’t be your first guess. According to scientists though, an 8850-kilometer-long belt that extends from West Africa to the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico is now officially the largest ever recorded macroalgal bloom. To top it off, the same researchers say recurrent blooms like this could become the norm.

The authors of the study published in Science call it the great Atlantic Sargassum belt and suspect the nutrients that make it up are a product of fertilizer runoff and deforestation, running off into the Amazon River and into the ocean in the summer. The extra nutrients are eaten up by the brown, grape-like seaweed, causing the bloom to grow larger and larger every year when scientists track it — something they’ve actually been doing with this particular patch since 2011.

According to NOAA, “Turtles use sargassum mats as nurseries where hatchlings have food and shelter. Sargassum also provides essential habitat for shrimp, crab, fish, and other marine species that have adapted specifically to this floating algae. The Sargasso Sea is a spawning site for threatened and endangered eels, as well as white marlin, porbeagle shark, and dolphinfish. Humpback whales annually migrate through the Sargasso Sea. Commercial fish, such as tuna, and birds also migrate through the Sargasso Sea and depend on it for food.”

But the sargassum in such excess isn’t a good thing, researchers say. When it dies in the ocean, the bulbs sink and can kill corals as well as trapping marine life because it’s so dense. And along Mexico’s Caribbean coast, where the stuff washes up and blankets some beaches, tons of tourism revenue is being lost. According to the Guardian, the Mexican government has spent millions to clear sargassum from many tourist-heavy beaches, only to watch it wash right back up. The dying blooms not only smell and keep people away from beaches, but they are even changing the acidity of the water too.

“The ocean’s chemistry must have changed in order for the blooms to get so out of hand,” Chuanmin Hu, a University of South Florida marine scientist who led the Science study, said in a press statement.