The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasted back in March that the 2023-2024 El Niño was on its way out the door and, surprisingly, La Niña would be right on its heels. They released data just a month before that suggested the cooling pattern around the equatorial Pacific had about a 55 percent chance to develop in the summer months. By April, they delivered an 85 percent chance El Niño would be over by June (it was) and we’d be welcoming La Niña by the end of August. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology jumped on board and issued an official La Niña watch the following month.

There have only been 10 times on record where an El Niño flipped to a La Niña within the same year but 2024 looked like it was about to produce the 11th. And if you lived on the U.S. West Coast during the last one, you had reason to expect a wild winter out of that recipe.

Then those projections started to flip.

NOAA forecasters changed their messaging in July, saying the odds were dropping for its arrival (70 percent chance by August-October, 79 percent chance by November-January. In October, they told us we should still expect a La Niña winter but it wasn’t going to be a strong one. Only four La Niña events had developed this late in the year.

“La Niña is favored to emerge in September-November (60 percent chance) and is expected to persist through January-March 2025. A #LaNina Watch remains in effect,” NOAA announced on X.

Now we’re two weeks away from 2025 and still no La Niña. So what happened?

La Niña conditions are most likely to emerge in November 2024 – January 2025 (59% chance), with a transition to ENSO-neutral most likely by March-May 2025 (61% chance). A #LaNina Watch remains in effect. https://t.co/5zlzaZ1aZx pic.twitter.com/rpXrT6ovZi

— NWS Climate Prediction Center (@NWSCPC) December 12, 2024

Funny enough, NOAA forecasters are still expecting a La Niña, giving a 59 percent chance of one developing “shortly.”

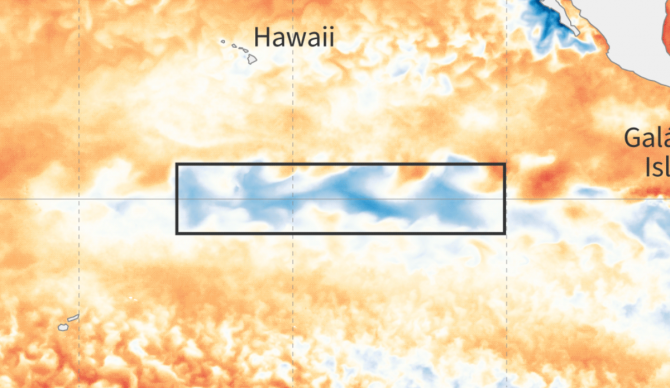

“The atmosphere looks like La Niña, and has for a while, but the ocean doesn’t, at least by our traditional sea surface temperature measures,” they wrote bluntly, adding that strong trade winds will cool the surface and “keep warm water piled up in the far Western Pacific.” When this happens (soon), conditions over the Pacific will cross into the La Niña threshold.

“But even if we do declare a La Niña Advisory soon, it will very likely be a weak event at most,” forecasters said.