Some 46 percent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is thought to consist of abandoned fishing nets. Image: The Ocean Cleanup

You have heard by now, of course, about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, or the GPGP. You know, of course, that it’s giant, and you know, of course, that it’s a very difficult problem. But did you know that it’s way bigger than previously thought? It is! Somewhere between four and sixteen times bigger, according to a new study published in Nature. Now, it’s estimated to be around 617,763 square miles.

“Our model, calibrated with data from multi-vessel and aircraft surveys,” reads the study’s abstract, “predicted at least 79 (45–129) thousand tonnes of ocean plastic are floating inside an area of 1.6 million km2; a figure four to sixteen times higher than previously reported. ”

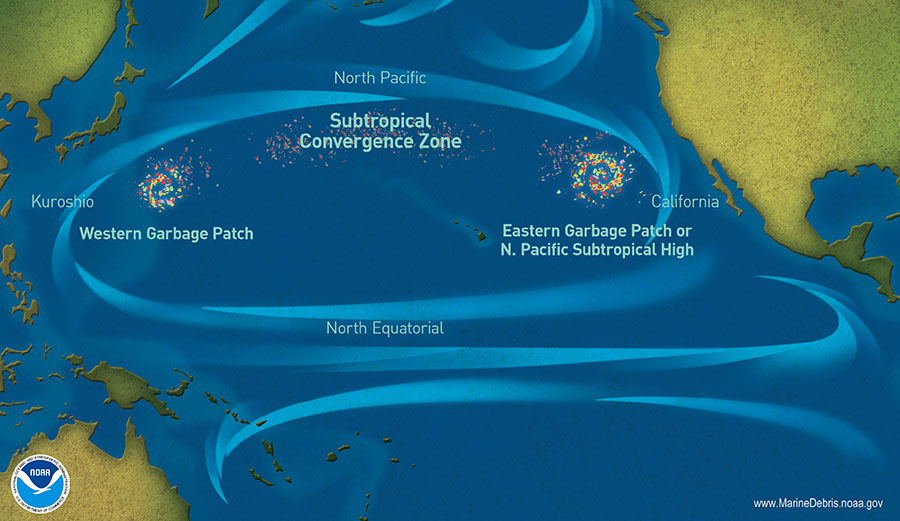

It’s been around for a long time, and in the last little while it’s received as much attention as it should. Researchers have also found numerous patches around the world, all caused by rotating ocean currents called gyres and our constant global plastic diarrhea. “Bigger than Texas!” used to be the tagline for the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Texas is 269,000 square miles. “Almost as big as Alaska!” is the new tagline. Alaska is 663,000 square miles.

It was back in the ’80s that researchers first noticed the floating accumulation of our trash. It’s not what you might think, though—while many visualize it as an actual island of floating garbage, it’s a little more complicated. It consists of all sorts of detritus including tiny pieces of plastic known as microplastics all the way up to fishing nets Much of it floats beneath the surface, making the actual size very difficult to gauge.

Image: NOAA Marine Debris Program

The increase, according to the study, isn’t all because of more garbage, although that’s certainly part of it. Because of better surveying techniques, we’re able to more accurately measure the true scale of it. The study was done by The Ocean Cleanup, the non-profit run by everyone’s favorite Dutch boy-genius, Boyan Slat. Slat’s team estimates that all the garbage in the GPGP weighs in at nearly 80,000 tons.

“Global annual plastic consumption has now reached over 320 million tonnes with more plastic produced in the last decade than ever before,” the authors of the study write. “A significant amount of the produced material serves an ephemeral purpose and is rapidly converted into waste. A small portion may be recycled or incinerated while the majority will either be discarded into landfill or littered into natural environments, including the world’s oceans.”

Microplastics, which have become something of an environmental buzz word as of late, make up about 8 percent of the patch, while abandoned fishing nets make up a staggering 46 percent. It’s thought that as much as 20 percent of it comes directly from the 2011 earthquake and impending tsunami in Japan.

Another recent study projected that we’re not even close to figuring it out, either. If human behavior continues unabated, says the report, plastic pollution is on track to triple by 2025.

The research took three years to complete and used both air and sea surveys. “To be able to solve a problem, we believe it is essential to first understand it,” says Slat. “These results provide us with key data to develop and test our cleanup technology, but it also underlines the urgency of dealing with the plastic pollution problem. Since the results indicate that the amount of hazardous microplastics is set to increase more than tenfold if left to fragment, the time to start is now.”