Artificial light could change the patterns of ocean creatures. Photo: Umut Sedef//Unsplash

Amidst the vast expanse of our moonlit seas, artificial light brightens the night and pierces through the surface, causing disruption to unfold beneath the shimmering waves. While the plastics and oil that permeate the oceans may be what first comes to mind when one thinks of contamination, ecologists and biologists are delving deeper into the effects of another long-recognized form of pollution: light.

A team of researchers from England, Norway and Israel mapped the first global atlas of nighttime ocean light pollution, quantifying underwater light levels for coastal regions worldwide.

To determine the strongest sources of light intrusion, lead oceanographer and marine biochemist Tim Smyth of the Plymouth Marine Laboratory used a methodology that entailed combining a 2016 atlas of night sky brightness with twenty years of oceanic and atmospheric data records. The data treasure trove encompassed shipboard measurements of artificial light and monthly satellite data spanning from 1998 to 2017, aiding in the estimation of light-scattering phytoplankton and sediment prevalence. Intricate computer simulations were also used to shed light on how various wavelengths of light navigate the depths.

One dataset focuses on nighttime light pollution, while the other centers on ocean color, which divulges the water’s optical properties. Through their model, the scientists projected how artificial light from above the surface infiltrates and penetrates the depths below. By quantifying the underwater light levels, the study offers a glimpse into the potential biological response of marine species to this luminance.

Smyth emphasized the critical importance of these light levels for biological organisms. Until now, the true extent of its impact on marine ecosystems remained largely unexplored and understudied.

From offshore oil complexes to residential coastlines, the glare from anthropogenic development has the capacity to penetrate deep within the seas, shifting the behaviors and survivability for the species that live there. Because sensitivity to light varies depending on species, the research team honed in on one of the smallest of species, in order to assess impact up the food chain. Copepods, a tiny planktonic crustacean, spend the evenings near the surface of the ocean, using the sun and winter moon to navigate their plunge into the depths during the daytime, where they hide from predators.

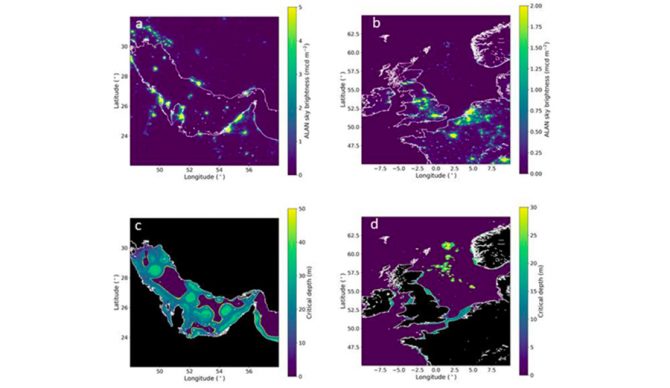

This graph shows artificial light at night (ALAN), sky brightness from the global atlas for the (a) Persian Gulf and (b) North Sea, two of the most ALAN-polluted regions on the globe (Table 2). In-water impact of ALAN shown as the critical depth (Zc) parameter for the (c) Persian Gulf and (d) North Sea.

The team found that within the top meter of seawater, the impact of artificial light is strong enough to cause a biological response across nearly two-million square kilometers of ocean, an area roughly three times the size of Texas. However, the penetration of light is not solely dependent on the intensity above the water’s surface; the optical properties of the water also play a role, and these can vary seasonally. For example, in regions with exceptionally clear water, such as parts of the South China Sea near Malaysia, artificial light at night can pierce through depths of more than 40 meters.

The most intrusive forms of light pollution occur in areas where offshore oil and gas platforms, coastal development, and wind farms are present. Furthermore, the shift towards energy-efficient light-emitting diode (LED) lighting, advocated by urban planners, may inadvertently pose challenges to marine ecosystems, warns the experts. Once illuminated by the warm, amber hues of sodium vapor lights, urban landscapes now emanate a stark and piercing blue glow, accompanied by a broader spectrum of light that holds the potential to impact marine species.

The study is a nod to scientists and where they should focus future studies of the effects of artificial light on marine life. Specifically, the study highlights areas where ecosystems are particularly stressed by artificial light, which could lead to rapid evolutionary changes and adaptation, Smyth said in a statement to NASA. Which is certainly something we need to keep track of.

Editor’s Note: Avery Schuyler Nunn is a California based writer, photographer, surfer, and science journalist.