La Niña is finally here. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced this week that conditions have officially formed to declare the weather event. That news comes after officials monitored its emergence through most of 2024 and first expected this winter’s La Niña to develop right on the heels of the outgoing 2023-2024 El Niño. The initial forecast is now for this La Niña to persist through April and transition to ENSO-neutral between March and May 2025.

“The atmosphere has been looking La Niña-ish for months, with stronger-than-average trade winds, more clouds and rain over Indonesia, and drier conditions over the central Pacific — all hallmarks of an amped-up Walker circulation,” Emily Becker wrote on NOAA’s monthly ENSO blog. “In December, the Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI), which measures the difference in surface pressure between the western and eastern Pacific, was 1.5 (positive values indicate a stronger Walker circulation). In fact, this is the fifth-strongest December EQSOI in the historical record. Drumroll… La Niña conditions have developed.”

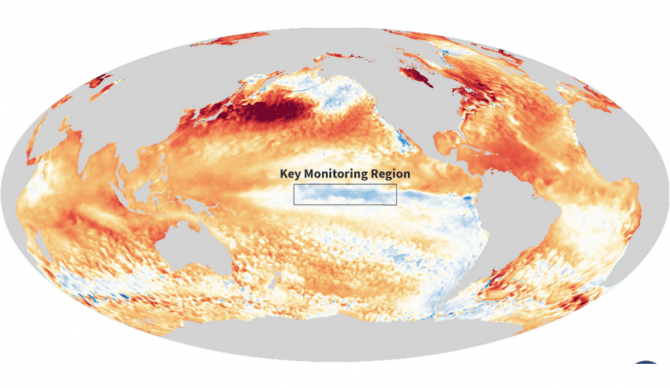

La Niña’s most often noted characteristic is the cooling of sea surface temperatures around the equatorial Pacific Ocean. El Niño, meanwhile, is driven by warmer-than-average temperatures in the same region. But those characteristics alone don’t determine whether or not we are in the midst of either weather event or what is called ENSO-neutral (the existence of neither El Niño or La Niña). Atmospheric changes from the cooling of those sea surface temperatures also need to exist as a result and forecasters follow a flow chart, per se, checking off certain conditions that eventually add up to the seasonal phenomenon.

According to the NOAA, sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean have hung around ENSO-neutral since April 2024. The threshold for La Niña conditions in that part of the checklist is -.5C below average. This past December the Niño-3.4 index was -0.6 °C. The atmospheric conditions needed for La Niña have actually been present for months, according to Becker, which included those “stronger-than-average trade winds, more clouds and rain over Indonesia, and drier conditions over the central Pacific.”

So, What Now?

As mentioned, this new La Niña is expected to last into the Northern Hemisphere’s spring months. The current odds of that are 60 percent, according to the administration, which leaves plenty of room for La Niña to last even longer than the predicted March-May index. What forecasters are most confident in at this point is that this year’s La Niña will be a weak one in part because the weather event emerged so late.

“It’s totally not clear why this La Nina is so late to form, and I have no doubt it’s going to be a topic of a lot of research,” Michelle L’Heureux, head of NOAA’s El Nino team told The Associated Press.

La Ninas tend to cause drier weather in the Southern and Western regions of the United States while other parts of the country experience wetter weather — conditions that had already been in play the past few months. A more active Atlantic hurricane season is also a common product of La Niña. This past Atlantic hurricane season was in fact more active than usual but that was without the presence of a full-blown La Niña. And as it stands now, La Niña is expected to have passed by the time the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season arrives.