You’ve heard it before. That age-old question: To build or not to build. As far as developers wanting to break ground on top of historic landmarks and Indian burial grounds, you may have never given it much thought. But when it comes to the mountains, well, that’s another story. Just ask the folks in the 2001 snowboarding cult classic, Out Cold. (And while you’re at it, ask the folks at Rotten Tomatoes why they only gave that movie an 8%.)

Sweetgrass Production‘s latest release (in conjunction with Patagonia), Keep Jumbo Wild, takes us to the Purcell Mountains of British Columbia, where for the past 24 years, conservationists and backcountry enthusiasts alike have been fighting developers over the construction of a sprawling ski resort.

More skiable acres?! What’s wrong with that? Well, imagine if you called BC home, and Jumbo happened to be your favorite local powder stache. It was never tracked out like all those other nearby resorts. There were no lift lines — or lift tickets for that matter. It was completely yours. You might be one of the many locals saying, “don’t take our mountain!”

Calgary Herald

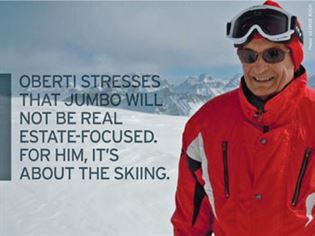

On the other side of the coin you have Vancouver uber developer Oberto Oberti. (If this were an 80s “ski school” movie, there would be a scene with him ordering an espresso at the local watering hole while our beloved ski heroes stand in the corner shotgunning PBRs.) Villainizing Oberti would be easy. But in staying true to proper documentary filmmaking, Patagonia’s film tells his side of the story, too. His actions may be that of an aggressive businessman, but his interest in a Jumbo resort no doubt stems from a love of skiing and the outdoors. At least all sides have that in common.

I found myself continually impressed by his ability to defend himself against personal attacks on his character. He speaks about the beauty and texture of untouched powder as only a true believer can. And when he reflects on his desire to enter the ski industry because of his genuine love of skiing and the outdoors, you sort of believe him. For someone who clearly values the beauty and texture of untouched powder residing under a bright blue sky, I’m surprised that he so willingly accepts the role of villain.

Biv.com

Nonetheless, here we are. Do we keep developing, a la Europe, or try to preserve some of the last vestiges of the “Western frontier?” As someone who just moved from the East Coast to Colorado, I’m surely enthralled by the romantics of a Western frontier. I was attracted to the same things that seduced generations before me: outdoor activities, clean air, small-town living, and spectacular views during the commute to work.

If it weren’t for the big resorts, I’d never have developed the skills nor the passion that’d lead me to a backcountry haven like Jumbo. However, I fully appreciate the view that with so many resorts surrounding the area, it’s unnecessary to develop more untouched land.

I live in Vail, surely one of the more developed ski towns in America. But when I walk through the village, despite its plethora of expensive clothing shops and skiing-related chain stores, I still feel like I found a Western frontier. For those of us that grew up near cities, I wholeheartedly believe that ski towns, commercialized or not, constitute that vision. To the dismay of many, we may have to come to terms with the idea that our “Western frontier” is now dotted with ski resorts and high-end stores. But having lived in New York and Washington D.C., Vail very much feels like a stop along the Oregon Trail.

Vail

Earlier this fall, I lucked into a backcountry stash along I-70, thanks in large part to some hitchhikers that traded its location in exchange for a ride to the top. It was truly my first experience skiing untouched backcountry snow. An amazing sensation, no doubt, enhanced by the ever-looming threat of avalanches and hidden rocks. I was hooked. I’ve been frequenting this location and plan on returning to it throughout the winter.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. How does that possibly qualify me to understand the struggle of the citizens of Jumbo? I obviously can’t fully understand their emotional connection to the land desired by Oberti. That said, if all of a sudden some big-time developer made plans to build a resort on my new secret location, I would be pissed—no, livid—that some corporate fat cat was taking away my personal powder stash. So, if I multiplied that hypothetical anger by 10, and then reinforced it with twenty-fours year of contentious history, I could more closely relate with skiers in the Jumbo Valley.

The citizens of Jumbo, some of them born and bred in towns removed from the hustle-and-bustle of big cities, have a legitimate gripe with the development that follows ski resorts. As Patagonia’s movie astutely points out, ski resorts stopped making money off of lift tickets in the 90s—much like movie theaters no longer make profit off of ticket sales. Thus, the introduction of a resort in Jumbo would lead to a great deal more development than just a couple of lifts entrenched on the slopes. Expect mansions, stores that sell jackets worth $2,000, and five-star restaurants. Those additions would absolutely inject capital into the area. Although, as the movie portrays, residents seem to be perfectly content as is.

Skicanadamag.com

As a skier, would I have been upset with the commercialization of Jumbo before seeing this movie? The short answer is no. And trust me, I feel bad writing that. I would rather be on team conservation than team commercialization. But I would be more likely to ski there if there was a resort attached to it.

However, this movie certainly altered my perspective. But not because of the loss of backcountry terrain.

I live along I-70 in Colorado, a stretch of highway littered with ski resorts and their typical accouterment. There’s still plenty of backcountry terrain available to the more dedicated riders out there. And I think that will remain true for some time.

What would upset me is that after such rampant objection, as detailed in Keep Jumbo Wild, big business could still win. Maintaining the Western frontier is important, if not essential, and although my vision of such a way of life may be different from that of the people of Jumbo, their commitment to a wild west must be honored. Does that mean that we have to yield to every protest for a ski resort for time eternal? Not necessarily. But if the residents of Jumbo, with an assist from one of the largest outerwear companies in the world, can’t hold onto their sacred land, then we may be headed towards the unhindered destruction of the Western frontier. And that would be the greatest tragedy of all.