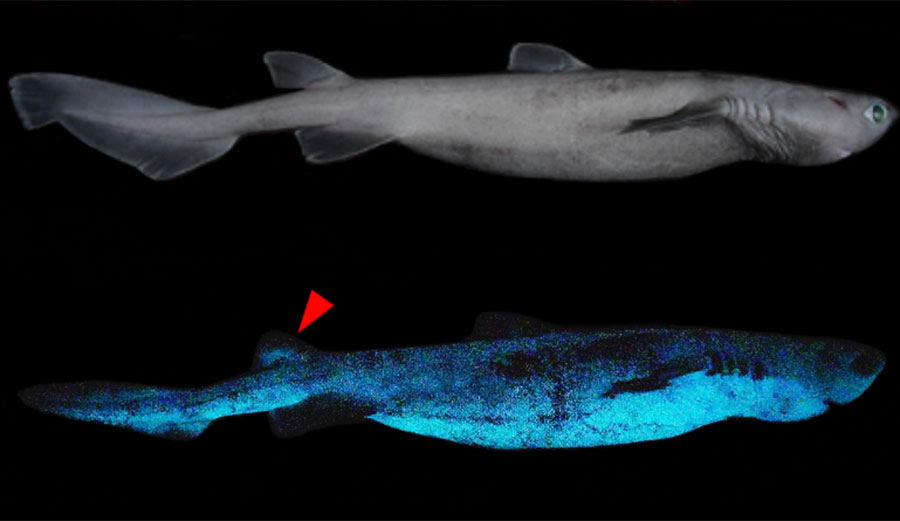

Lateral and dorsal luminescent pattern of Dalatias licha, aka the kitefin shark. Photo: Mallefet/Louvain/Frontiers in Marine Science

Researchers have known for a while now that some sharks can glow in the dark. But not many. Until recently, it was only thought that around a dozen species lit up in the dark depths of the ocean. A new study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science reported that three more can do it, and one species, the kitefin shark, can grow up to six feet in length.

The discovery was made when shark researchers were poking around off the eastern coast of New Zealand, and it adds a whole lot more information to the bioluminescence canon. The expedition, in which the researchers pulled blackbelly lanternsharks, southern lanternsharks, and kitefin sharks up from an area of the deep sea known as the “twilight zone,” was yet another reminder that there’s still so much going on in the ocean that we don’t know about. The twilight zone is the region from a depth of 660 to 3,300 feet, where, as the name implies, light filtering down from the surface is scarce.

“Bioluminescence has often been seen as a spectacular yet uncommon event at sea but considering the vastness of the deep sea and the occurrence of luminous organisms in this zone,” wrote the authors of the study, “it is now more and more obvious that producing light at depth must play an important role structuring the biggest ecosystem on our planet.”

The voyage took place just over a year ago, in January of 2020. Jérôme Mallefet, the lead author of the study, along with a crew of scientists from the Université Catholique de Louvain and New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, spent a month aboard a vessel called the R.V. Tangaroa. Their method was surprisingly simple: they caught the sharks, placed them in a large tank full of seawater, and took them in to a dark room. There, they watched the sharks to see if they’d light up with bioluminescence. Animals that are bioluminescent have special cells in their skin that can emit a soft blue-ish light.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the sharks’ biofluorescence is that, up until 2016, only other sharks could see it. Realizing there was something else going on that humans couldn’t see, researchers examined shark’s eyes and were able to build a special camera that showed us how they see.

What’s interesting about the shark bioluminescence, however, is that it’s a little different than other creatures that have it. Fireflies, for example, have a chemical called lucifern in their cells that produces light. Deep-sea angler fish produce their light by hosting bacteria that bioluminescence. But sharks remain something of a mystery: when Mallefet and the other scientists sampled the sharks’ skin, they found neither lucifern or bioluminescent bacteria. Instead, they discovered that the three species of sharks controlled their light with hormones — specifically melatonin. In mammals, of course, melatonin is the thing that makes us sleepy.

The obvious question, aside from the how, is the why. Researchers believe that, in a nearly pitch black environment, the ability to create light might be helpful in identifying friends, attracting prey, deterring predators, or even camouflaging themselves. Since the twilight zone’s tiny amount of light filters down from the surface, it would make sense that the sharks’ bellies would be able to light up more than their backs — to help them blend in with the light from the surface — and the researchers did, indeed, find just that.

Interestingly, however, the kitefin sharks had high concentrations of the bioluminescent cells in their dorsal fins, a trait that Mallefet believes might be a way for them to communicate.

“A lot of people know that sharks can bite, thanks to Jaws,” Mallefet told National Geographic, “but few people know that they can glow in the dark.”