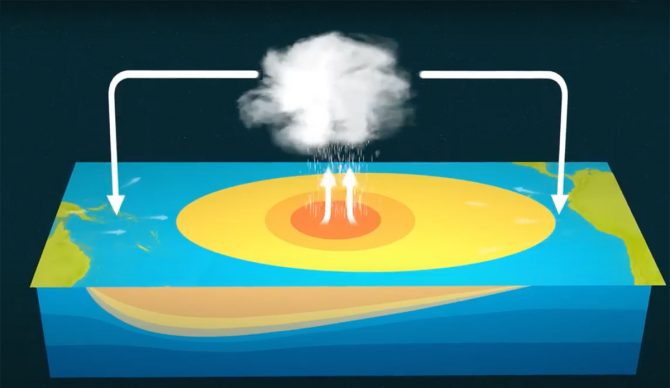

El Niño changes rainfall patterns over the equatorial Pacific and can affect global weather. Image: Met Office//YouTube

For the last few months, North America has been slammed by some pretty weird weather events. It has mostly been a function of a strong El Niño that boosted average temperatures in 2023. That in turn amplified the atmospheric rivers that have been — and currently are — drenching much of the West Coast. El Niño also had a helping hand in the heat waves that hit the South and the Midwest over the summer. But as time wears on, El Niño appears to be wearing out. According to experts, it’s likely that El Niño is on the road to weakening and could be gone by late spring or early summer.

El Niño, as you are most likely aware, is “a warming of the ocean surface, or above-average sea surface temperatures, in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean.”

Low-level surface winds generally blow from the east to the west along the equator. In an El Niño year, those winds weaken or even blow from west to east. While no two events are exactly alike, they can affect weather patterns all over the world. An El Niño year is heralded by warming waters building along the equator off the coast of South America paired with that change in the prevailing winds. “Every three to seven years or so, however, these winds relax or turn to blow from the west,” explains Paul Roundy, a Professor of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences at the University at Albany. “When that happens, warm water rushes to the east. The warmer-than-normal water drives more rainfall and alters winds around the world. This is El Niño.”

For the duration of the El Niño event, those waters stay warm until they are cooled are driven away from the equator by a return to normalcy in trade winds. On the flip side, a La Niña year is caused by abnormally cold conditions in the eastern Pacific.

This year’s El Niño looks as though it probably reached its zenith in December, but as of this writing, it’s still going strong. Forecasts are predicting that El Niño conditions will likely continue to favor unusual warmth in Canada and the northern United States and occasional stormy conditions across the southern states before it begins to taper to a level not quite so damaging.

“El Niño is likely to end in late spring or early summer, shifting briefly to neutral,” Roundy continues. “There’s a good chance we will see La Niña conditions this fall. But forecasting when that happens and what comes next is harder.”

So what can we expect, weather-wise, in the coming months? Like Roundy said, that’s a bit of a tough one. As is the norm, forecasters use past events to gauge how the present one might act. Take, for example, the El Niño event of 1998. While the surface waters were still warm in the eastern tropical Pacific in May of that year, the colder waters were just a few feet below the surface. All it took was a few days of moderate winds to pull that cold water up to the surface. That effectively turned El Niño off. A few years prior, in 1987, another El Niño struck. That one, however, stuck around until December, although it was significantly less potent due to the fact that it backed off into the central Pacific.

In early February of 2024, strong winds were still pushing to the east in the equatorial Pacific, which generally adds a few months to El Niño’s existence. But those winds, if they’re strong enough, can also push that warm water out of the tropics, which increases the chances of an El Niño reversal by the fall.

One of the most important bits of El Niño’s effects is that it can serve to dampen hurricane activity in the Atlantic.

“El Niño’s Pacific Ocean heat affects upper level winds that blow across the Gulf of Mexico and the tropical Atlantic Ocean,” writes Roundy. “That increases wind shear – the change in wind speed and direction with height – which can tear hurricanes apart. The 2024 hurricane season likely won’t have El Niño around to help weaken storms. But that doesn’t necessarily mean an active season.”

That last fact might seem at odds to the 2023 Atlantic hurricane season, but that’s because El Niño’s pull on the winds was offset more that usual by abnormally warm water in the Atlantic. Those waters, of course, are the fuel for hurricanes.

This most recent El Niño has been a strange one. It came after three years straight of La Niña years — an exceedingly rare event called a “triple dip” — and instead of a slow build, it developed very quickly. According to Professor Roundy, “the combination led to weather extremes unseen since perhaps the 1870s.”