Nearly one million flip flops now live on the islands. Image: Silke Stuckenbrock/Nature

Have you ever been to a tropical paradise? You know the type: palms sway gently in the breeze, white, soft sand your feet, high, wispy clouds flit about in a blazingly bright blue sky, and, if you’re lucky, some far off wave fires through crystal clear water over a jagged reef. If you have, then you are likely aware that there are no paradises that aren’t marred by bits and pieces of our daily life. Plastic floats from our dirty doorsteps onto those beaches. We use it for convenience, crabs use it for houses, and birds use it for food. Well, a marine biologist exploring a remote string of islands in the Indian Ocean found a tropical paradise that is basically more trash than island. The study that came from the trip was published recently in Nature.

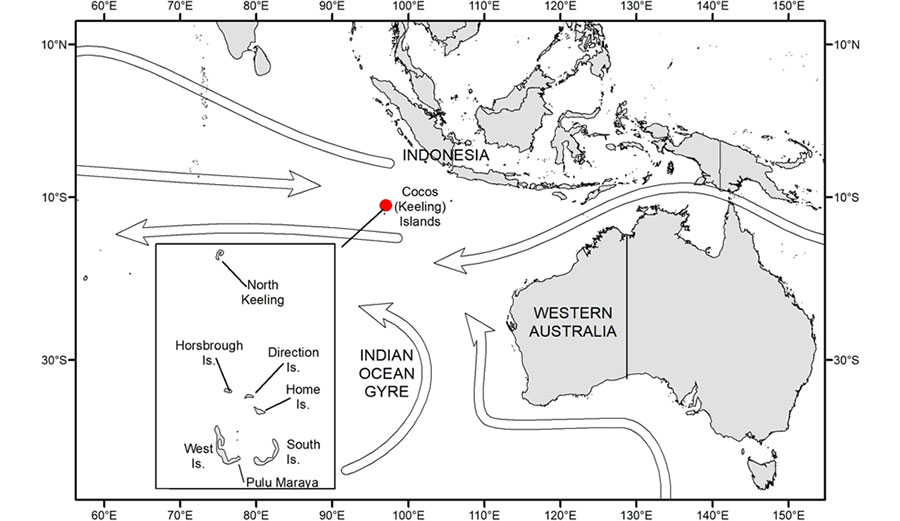

Jennifer Lavers, a research scientist at the University of Tasmania in Australia, headed to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands—tiny little patches of land that sit about a 1,000 miles from the northwest coast of Australia—to measure plastic waste in an area where no one lives. Since the islands are basically devoid of human life, it was a good place to go. There simply aren’t enough people who call the island home to throw toothbrushes and plastic bags into landfills. One would assume, then, that the island would be relatively free from the detritus of everyday life. Oh, how wrong one would be in their assumption!

Tiny little islands. Tons of garbage: Image: Nature

Among the garbage that has floated to the string of islands, Lavers found 373,000 toothbrushes and around 975,000 shoes, largely flip-flops. Now, she estimates that the 27 islands that make up Cocos Keeling play host to some 414 million pieces of plastic debris.

Of the 27 islands, Lavers and her team looked at seven. Conducting their research for the majority of 2017, they marked off sections of beaches, counted the plastic in them, then took the total amount of beach area that make up the rest of the islands and did a simple multiplication. The team dug 4 inches down into the sand, and found the deeper they went, the more plastic there was. “We estimated that what was hidden below the sediment was somewhere in the range of 380 million pieces of plastic,” Lavers told NPR.

Anthropogenic debris on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, March 2017. (A) eastern side of South Island, (B) north side of Direction Island, (C) beach-back vegetation along the north-east side of Home Island, (D) micro-plastics (primarily; 1–5 mm) along the eastern side of South Island. Images: Nature

Lavers isn’t new to this kind of research, but even she was floored by the results. “You get to the point where you’re feeling that not much is going to surprise you anymore,” she said. “And then something does … and that something [on the Cocos Keeling Islands] was actually the amount of debris that was buried.”

This, of course, is not news to you. The superabundance of the tools of our convenience in our oceans, on our beaches, and in basically everything is a constant source of frustration. For many researchers, it must feel a bit like the horse they’re beating has been smashed to a bloody pulp. Still, though, they go on beating it in hopes that something will click at a level high enough to affect meaningful change. “In the absence of meaningful change, debris will accumulate rapidly on the world’s beaches,” the researchers wrote in their paper. “Small, buried items pose considerable challenges for wildlife, and volunteers charged with the task of cleaning-up, thus preventing new items from entering the ocean remains key to addressing this issue.”