Instead of waiting in line for cheap prices on gear, REI is encouraging people to #OptOutside. But can consumption ever really be green? Photo: daveynin/Flickr

While shoppers scramble for Black Friday bargains this year, outdoor retailer REI is closing its 145 U.S. stores. This is the second consecutive year the Seattle-based company will ignore the frenzy that traditionally marks the start of the holiday shopping season. REI’s nearly 12,000 employees will get a paid holiday and will not process any online orders. Instead, REI exhorts workers and customers to get outside with family and friends. It has even coined a Twitter hash tag, #OptOutside, to promote the event.

Some observers have praised REI for mixing business savvy with crunchy acumen. Its #OptOutside campaign is an example: By encouraging customers to reject Black Friday-style excess, the promotion burnishes REI’s reputation as a progressive retailer.

But how did REI and other outdoor companies align themselves with conservation? How do they square selling expensive apparel and promoting carbon-spewing tourism with their customers’ love for the outdoors? And how radical is “Green Friday,” especially if the OptOutsiders are carrying backpacks stuffed with the latest gear made from precious petroleum, rare metals and pricey fibers?

The answer is that shoppers have long expressed their affection for nature in what they buy. Consumption and environmental concerns, past and present, fit together as snugly as a foot in a beloved hiking boot.

Consuming nature, dividing people

The paradoxes of modern outdoor retailing have deep roots in the American conservation movement. In the late 19th century, early conservationists such as John Muir grew alarmed as they saw wildlife decimated, forests denuded and scenery despoiled. Among the loudest protesters were affluent outdoorsmen, such as Theodore Roosevelt, founder of the Boone and Crockett Club, and William Temple Hornaday, first director of the New York Zoological Society.

Class differences pervaded other forms of outdoor recreation too. People with means vacationed at posh resort hotels. Middling Americans took more rustic routes. Outdoor groups such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, founded in Boston in 1876, and The Mountaineers, founded in Seattle in 1906, taught woodcraft to middle-class urbanites who yearned for authentic escapes.

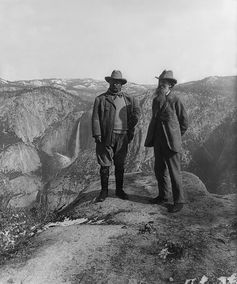

President Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir on Glacier Point, Yosemite National Park, 1906. Photo: Library of Congress/Wikipedia

By calling to protect nature, these conservationists also protected their own hunting and fishing entitlements. They attacked the rural poor, immigrants and minorities, who Hornaday once called the “regular army of destruction” because they took fish and game for subsistence or sale. They used their money and power to license hunters and anglers, limit harvests and ban equipment. Some of these measures protected nature (and still do), but they also intentionally reserved nature for those who could consume it properly by the standards of wealthy conservationists.

Others chafed against even these austere types of play, seeing outdoor recreation as a costly privilege. They mobilized leisure as political protest. Seattle’s Co-Operative Campers, launched in 1916 as a cheaper alternative to The Mountaineers, pledged to “make our mountains accessible through co-operative camps” for the city’s blue-collar citizens. Socialist activist Anna Louise Strong was the Co-Op Campers’ first president. She and the Co-Op Campers often clashed with The Mountaineers over politics and camping techniques until the club disbanded during the 1920s Red Scare.

REI took root in this contested consumerist soil. Lloyd Anderson, REI’s founder, conspired with other members of The Mountaineers to promote riskier activities, such as rock climbing. He quickly learned that they did not have the requisite gear. Influenced by other local co-ops, Anderson organized REI in 1939 to pool members’ annual fees so the group could purchase quality equipment from Europe at affordable prices.

As costs for lightweight materials such as aluminum and nylon fell after World War II, REI attracted a burgeoning following locally and nationally. And it continued to trade on its founders’ cooperative and environmental vision. In 1976, a year after opening its first retail store outside of Seattle, it launched an environmental grants initiative, and in 1989 the firm cofounded the Conservation Alliance, a group of outdoor businesses dedicated to environmental protection.

Gunstock Campground and Recreation Area, Guilford, New Hampshire, 1961. Photo: Eric M.Sanford/Flickr, CC BY-NC

Yet REI’s #OptOutside campaign can seem superficial compared to more radical stances. Patagonia, founded in 1973 by Yvon Chouinard as a spin-off from his self-named climbing equipment company, has promoted recyclable clothing, and applied tough sustainability standards to its global supply chains. In its 2013 “Don’t Buy This Jacket” campaign, Patagonia even encouraged customers to make do with less.

Critics have accused Patagonia of playing the snob card and promoting chic travel to imperiled and faraway places. Chouinard himself freely accepts these accusations. As he cynically admitted in a recent New Yorker profile, “everyone’s just greenwashing,” because “growth is the culprit.”

In this context, REI’s Black Friday campaign can look like an unabashed marketing ploy that ignores the fundamental source of our environmental problems: humans’ overuse of the earth’s resources. Other businesses have deployed similar devices to entice earnest consumers, with mixed results, from fair trade coffee, which may not be economically viable, to sustainably sourced seafood, which may not be that sustainable.

Maybe Chouinard is right: we are all being greenwashed.

Is green good – or possible?

But is this a bad thing to admit? Perhaps. To deny the inherent contradictions of Green Friday is to ignore how affection for nature collides with our longing to consume it. By asking customers to think about what they are buying, Patagonia tries to foreground the environmental and social ethics of buying a new fleece jacket. REI, by contrast, asks us to take a one-day shopping holiday to help the planet. At best it is a lighter green vision.

The L.L. Bean flagship store in Freeport, Maine, open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Photo: Shutterstock

However conservation-friendly they may be, REI and its competitors are businesses, and none of these efforts supersede retailers’ bottom lines. Moreover, enlisting environmental concerns to drive sales or political change is nothing new. Greenwashing is just the latest term for an old phenomenon: tethering consumption to environmental values. In turn, consumers have proclaimed their environmental values through purchasing power since the dawn of the conservation movement.

Ultimately, there is no such thing as truly green consumption. Take the alternative to Black Friday: Cyber Monday, just after Thanksgiving, when retailers seek to entice consumers to spend online with early holiday discounts. Is internet shopping better for the environment than driving to the nearby mall? It may keep us off the road, but online shopping does not eliminate environmental costs – it just diverts them to the data warehouses that power retailers’ mail order divisions, and the planes and trucks that deliver the goods to consumers.

This Thanksgiving, while arguing politics over holiday spreads, take time to remember the late biologist Barry Commoner’s famous aphorism: There’s no such thing as a free lunch.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article here.