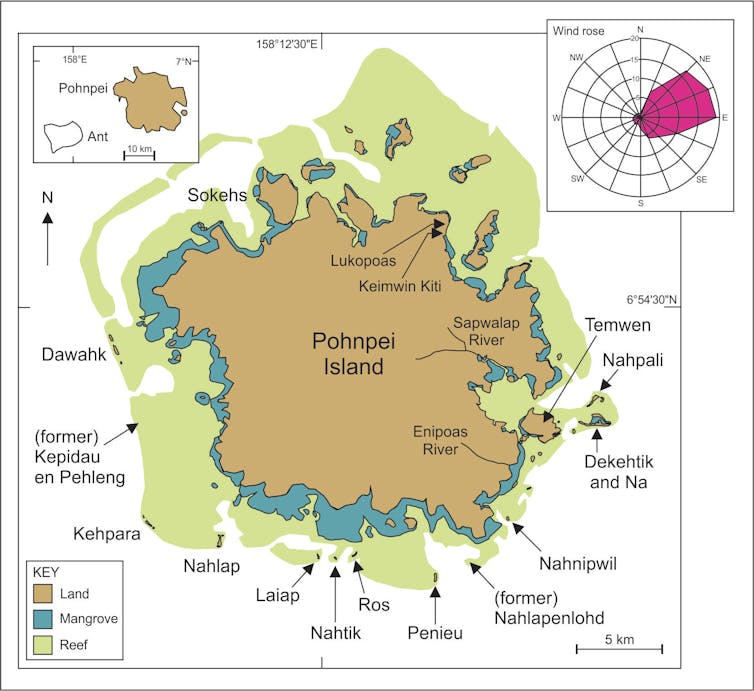

Laiap, to the west of the site of the now-disappeared Nahlapenlohd.

At first glance, it may not seem so, but the story of the now-vanished island of Nahlapenlohd, a couple of kilometers south of Pohnpei Island in Micronesia, holds some valuable lessons about recent climate change in the western Pacific.

In 1850, Nahlapenlohd was so large that not only did it support a sizeable coconut forest, but it was able to accommodate a memorable battle between the rival kingdoms of Kitti and Madolenihmw. The skirmish was the first in Pohnpeian history to involve the European sailor-mercenaries known as beachcombers and to be fought with imported weapons like cannons and muskets.

Today the island is no more. The oral histories tell that so much blood was spilled in this fierce battle that it stripped the island of all its vegetation, causing it to shrink and eventually disappear beneath the waves.

Like many oral tales, this one tries to explain island disappearance post-1850 by making reference to an historical event. But in light of what we know today, the more plausible cause of the island’s disappearance is the sea-level rise in the western Pacific since the early 19th century, which has accelerated significantly over the past few decades. The disappearance of islands in the Solomon Islands in the southwest Pacific has recently been attributed to sea level rise. Further north, the same is true of several reef islands off Pohnpei.

CREDIT, Author provided

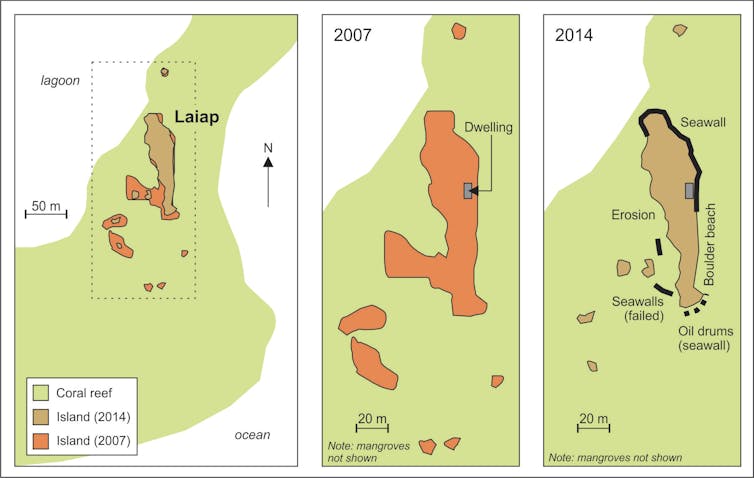

Surveys of 12 of these islands have shown that not only have some – like Nahlapenlohd – completely disappeared, but that most others have shrunk over the past decade. Islands such as Laiap and Ros, which have lost two-thirds of their land area over this time, are likely to disappear completely within the coming decade.

CREDIT, Author provided

Why are islands in the western Pacific becoming the earliest casualties of sea-level rise? Partly because sea levels in this region have risen at two to three times the global average over the past few decades.

In parts of Micronesia, sea level has risen by 10-12mm each year between 1993 and 2012, far outpacing the global average of 3.1mm a year. While this rate is unlikely to be sustained indefinitely, the current trend would raise sea levels by a further 30-40cm by mid-century if it were to continue.

What’s more, reef islands are particularly vulnerable to erosion by rising seas, being made almost entirely of sand and gravel. Whole islands – even some island nations with which we are familiar today – are likely to be rendered uninhabitable or even disappear within the next 30 years. These include islands in nations like Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Tokelau and Tuvalu, as well as some in other island nations that comprise mostly larger islands, such as the Federated States of Micronesia, of which Pohnpei is one.

Armored islands

Yet we should note that not all of Pohnpei’s reef islands are disappearing, at least not at the same rate, and some have fortuitously evolved protection that will likely help them outlive their neighbors.

The coasts of some islands – like Kehpara and Nahlap – are “armored” by beaches of huge boulders left there by large storms, often along their most exposed coasts. Other reef islands off Pohnpei’s leeward coast, such as Dawahk, are becoming “skeletonized” as waves wash across the island removing the sand and leaving only rocks, held in place by a maze of giant mangrove roots.

Whether or not the islands themselves succumb or survive, sea-level rise is a clear threat to their habitability for humans. Short-term interventions – either natural fortifications such as boulder beaches or human-built defences such as seawalls – are unlikely to change the long-term outcome.

This underscores the fact that low-lying reef islands are transient – most Pacific reef islands formed only in the past 4,000 years after sea levels fell and sediment began to pile up on exposed reef platforms. The sea will remove today’s islands, just as it has washed away countless others before.

But of course, we cannot ignore the human dimension. While only a few dozen people today call the reef islands of Pohnpei home, they are similar to many larger reef islands in Micronesia from which people may well be involuntarily displaced during the next few decades. Where these people might go, and how they can be accommodated in ways that preserve their dignity as well as their unique cultures, are very real questions for community leaders.

People first reached the islands of Micronesia from the Philippines, about 3,500 years ago after an unbroken ocean crossing of 2,300km. It’s an extraordinary achievement when you consider that people in most other parts of the world at that time rarely sailed out of sight of land. To have survived on islands in the middle of the ocean for more than three millennia, Micronesians and other Pacific Islanders must have developed considerable resilience.

On high islands in Micronesia, the evidence for this is manifest. Ancient stonework constructions line many parts of the coastline, testament to a long

history of resisting shoreline change, and sometimes of manipulating it for human advantage.

Perhaps nowhere is more evocative of this today than Nan Madol, a megalithic complex built 1,000 years ago on 93 artificial islands off southeast Pohnpei. There are many explanations about why Nan Madol was created. Perhaps the truth is that it is an expression of dogged human resilience – one of hundreds along Micronesian coasts – in the face of an unruly nature.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.